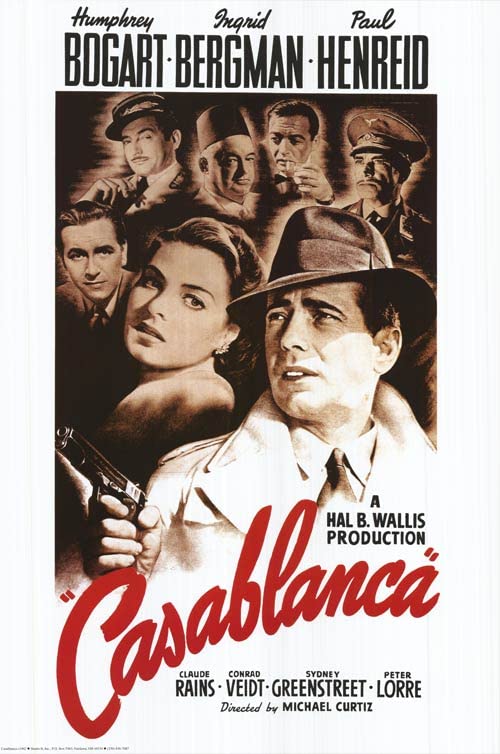

This week we return to screenplay analysis, and the screenplay we’re analyzing is CASABLANCA. Listen to why Joe thinks this is the greatest screenplay ever written.

Some links in this episode:

You can listen to it here.

And here’s the script of the episode.

Hi, this is Joe Dzikiewicz, and welcome to the Storylanes Podcast, the podcast where I analyze screenplays and talk about how I’m making an independent feature film. Yup, that’s right: I’m hard at work producing DOMICIDAL, an independent horror film. It’s the story of a cantankerous feminist tech podcaster who is making a podcast about living in a smart-tech home. But there’s a problem: the house is haunted. Or so it seems, because all that smart home technology is controlled by a hacker. It’s as if your worst enemy in the world controlled your Alexa.

This week I have what I hope you will consider to be a treat. I know I consider it to be a treat. Because this week, I’m going to turn back the clock. Turn it back to the first season of this podcast. But also turn it back to 1942, when World War II was raging and when classic Hollywood was at its best.

If you’ve been listening to this podcast for a while, you know that the first season was all about analyzing screenplays. I did a deep dive analysis of the screenplays of fifteen different movies, ranging from Oscar winners like PARASITE to low-budget horror movies like IT FOLLOWS.

I really enjoyed doing those analyses. And I learned a whole lot. In my opinion, the best way to learn about screenwriting is to study the great scripts. And also to study the not-so-greats and try to figure out where they fall short. That was the original goal of this podcast.

But there was a problem. These analyses take a lot of time. To prepare one, I read the screenplay, watched the movie, did the analysis, wrote up the script for the episode, reviewed that script, recorded the podcast, edited it to remove all the uhs and ums and other verbal stumbles, review the edited podcast, put up the web page for the episode, and then and only then was I done. Each episode took almost two days of effort.

When I was pushing out an episode a week, I wasn’t working. So I had the time to spend. But then I went back to work, and then I got rolling on DOMICIDAL. And suddenly time is at a premium.

But I still think those analyses had huge value, both to me and to potential listeners. So I’m going to try to start publishing episodes like that again. Oh, I won’t be doing an episode a week. But I’m going to try to do one a month.

I’ll still give the occasional updates on DOMICIDAL progress. But if you want more detailed news on how that’s going, sign up for the DOMICIDAL newsletter at http://domicidal-movie.com.

But to the analysis. To celebrate my return to the Storylanes roots, I’m going to start with what I consider to be the greatest screenplay ever written. That’s CASABLANCA, screenplay by Julius and Philip Epstein and Howard Koch, based on a play by Murray Burnett and Joan Alison. CASABLANCA is generally considered one of America’s greatest films. It stands at number 3 on AFI’s list of 100 best American movies. But I’d rate it as number 1 – it’s my all-time favorite American movie. And in large part, I give it that rating because of the script.

Don’t get me wrong. The movie is excellently acted and directed. And the camera work is quite good, though not up to the levels of some of the greatest examples of American cinematography.

But oh, that screenplay!

As always, there will be spoilers in this episode. But really, if you haven’t ever seen CASABLANCA, what are you doing listening to a screenwriting podcast? It’s one of the pillars of American film. Do yourself a gigantic favor and see it now.

Now I’m going to be doing something a little different in this episode. Instead of spending a lot of time looking at Casablanca through the lens of all those screenwriting models, I’m going to focus on why I think it’s such a great screenplay. We’ll definitely get into the structure of the screenplay, because as William Goldman reminds us, Screenplay is Structure, and Casablanca has a great one. But I won’t spend a lot of time comparing its structure to “Save the Cat” or traditional three-act structure or the hero’s journey or any of that stuff. If you want to look at it through that lens, check out storylanes.com and the Casablanca analysis found there. Because as usual, I’ve included lanes in the Storylanes analysis for each of those models.

So what makes CASABLANCA so darned awesome?

Let’s start with the dialogue. Because CASABLANCA may be the most quotable screenplay ever written, with several lines that have become iconic and entered the language.

Now I should say, I love a good line as much as the next movie fan. But I don’t think dialogue is the most important thing about a screenplay. Story structure always comes first. While great dialogue can be great, it’s the icing on the cake. It’s not the cake.

That said, listen to a few of the lines from CASABLANCA. Because they’re truly amazing.

“I’m shocked, shocked to find that gambling is going on in here.” “We’ll always have Paris.” “Round up the usual suspects.” “Here’s looking at you, kid.” “Of all the gin joints in all the towns in all the world, she walks into mine.” “I came to Casablanca for the waters.” “Waters? What waters? We’re in a desert.” “I was misinformed.” “We haven’t quite decided whether he committed suicide or died trying to escape.” “Louis, I think this is the beginning of a beautiful friendship.” It goes on and on and on.

If all you want from a movie is some great lines that you can repeat on the way out of the theater, you could do a lot worse than CASABLANCA. In fact, you could hardly do better.

But that’s not all that this movie has. Because it has a nigh perfect blending of theme, story structure, and protagonist’s character arc. And that’s what we’re going to be diving into next.

CASABLANCA is the story of Rick Blaine, played in one of the great movie performances by Humphrey Bogart. Rick is a man who used to be one of those self-effacing heroes that were so beloved in that era. He was once an adventurer, always fighting on the noble but losing side. Even if, as Louis says, “The winning side would have paid you much better.”

But now, Rick has curdled in on himself. Now his motto is, “I stick my neck out for nobody.” He uses people, treats them terribly. “Where were you last night?” “That’s so long ago, I don’t remember.” “Will I see you tonight?” “I never make plans that far ahead.” Won’t even share a drink. “He never drinks with customers. Never. I have never seen him.”

CASABLANCA is the story of why Rick has gone so dark. And how he regains his heroic spirit, how he gets to the point where Victor Laszlo, the embodiment of heroism, can say to him, “Welcome back to the fight. This time our side will win.”

At the start, Rick has a major flaw. He’s awfully self-centered. And what he needs to learn is to put his own struggles and suffering in perspective. To put the needs of others above himself.

You get the feeling that Rick wasn’t always that curdled, but he was always that self-centered. He liked being the hero, liked how it made him feel.

And that ties him directly to the theme of CASABLANCA. Because the theme, as Rick states near the end of the movie, is, “It doesn’t take much to see that the problems of three little people don’t amount to a hill of beans in this crazy world.” In a world that is burning, individual needs and suffering need to take a backseat to the greater good.

This was a perfect blending of theme and time. Because CASABLANCA was made in 1942, in the middle of World War II. The world was a horror show, and individual problems had to take second place to the collective pains of the world. Every movie is obviously a product of its time, but CASABLANCA’s message seems particularly apt for its moment in history.

The major supporting characters of CASABLANCA tend to the extremes. Louis is about as corrupt and self-serving as one can imagine. Victor Laszlo as noble as noble can be. Major Strasser is a complete villain. And Ilsa is pure radiant beauty. Oh, she’s got a strength of character, to be sure. But as played by Ingrid Bergman and shot by cinematographer Arthur Edeson, she positively glows.

There’s a lot more characters in this movie, to be sure. But let’s talk about them a little later. Because they constitute one of the great strengths of CASABLANCA, and they are well worth a special discussion.

Instead, let’s dive into structure and theme and how it’s all wrapped up in Rick’s character arc.

The first thing we see in CASABLANCA is literally the entire world. Voiceover describes the situation: the world is at war, but Europe is occupied by Germany. And desperate people are streaming out of Europe, trying to escape the Nazis. And their way out takes them through Casablanca in French Morocco in northern Africa.

Notice how it does this. We start about as broad as we can get, with the whole world. From there we move quickly to Europe. And then we narrow in on Casablanca. And all the time we’re zooming in closer on a map.

Now this doesn’t only set the stage. It also sets the stakes. The whole world is at stake in Casablanca, and that’s critical to the final theme.

Once in Casablanca, we see desperate people trying to get out. We see unscrupulous people feeding on them. We see that there is an active resistance movement, but we also see that life is cheap. In five short pages, we know this place, know the issues that are facing the people stuck in it, know how it fits into the broader context of the world. It’s nice economic story telling.

We’re next introduced to a major source of the conflict as we meet the Nazi Major Strasser. And we’ve given a glance of the primary struggle at hand: the Nazis want to keep resistance leader Victor Laszlo, find some reason to arrest him.

But from there, our point of view narrows even further. Because next we find ourselves in Rick’s Café Americain. And this is where much of the film takes place.

Once again, we see desperate people trying to find a way out. Once again, we see the unscrupulous preying on them. All against a backdrop full of glamor. And finally we’re at the center of the action. We’ve gone from the World to Europe to Casablanca and now, finally, we’re at Rick’s. From broad to narrow, and all well done.

And the Rick we meet is Rick at his darkest. This is when he treats Yvonne like dirt. It’s when he refuses to stick his neck out to help Ugarte escape from arrest.

And it’s when Ilsa walks into Rick’s.

We know immediately there’s something there, something painful. And note how clever the screenplay is at making this clear, how it piles on the layers of signifiers. Note Sam’s reluctance in this clip:

Ilsa asks Sam, who we already know is devoted to Rick, to play “As Time Goes By.” Sam’s reluctance and reticience around Ilsa is the first sign something’s up. But he finally plays it. And then Rick storms over, angry. “Sam, I thought I told you never to play…” It’s the first time we see Rick be anything but cool and cynical, and it’s all because of that song. And when he sees Ilsa, he’s shocked.

But they can’t process yet, there’s too many people around. All they can do is a bit of coded talk full of subtext. “That was the day the Germans marched into Paris.” “Not an easy day to forget.” “No.” “I remember every detail. The Germans wore gray. You wore blue.”

And that’s pretty much the end of that sequence. All the main pieces are on the table. We’ve met Rick. We’ve gotten a hint of his pain. We’ve met Ilsa and Laszlo, Major Strasser and Louis. And we’ve met Casablanca and learned of the desperation of the people stuck there.

It’s a terrific opening.

What follows next is rather interesting. In most movies, and as prescribed by most screenwriting gurus, the protagonist should reach his lowest point about two-thirds of the way into the movie, right near the end of act two. Everything has piled up on our hero and he looks like he’s going to collapse under the weight. Which means that when he comes back fighting, it’s all the more exciting.

But in CASABLANCA, Rick’s dark night of the soul takes place here, right at the end of act one. This is the moment when Rick, in his cups, repeatedly orders Sam to play “As Time Goes By,” when he wallows in his memories of his Paris romance with Ilsa. When we see the flashback of a happier Rick in happier times. When we see the flashback of the moment that broke him, when Ilsa abandoned him at the train station.

Rick receives other blows in the course of the movie. But this is his lowest point.

And this, of course, is when Ilsa enters. And Rick is brutal to her.

“I heard a story once. As a matter of fact, I’ve heard a lot of stories in my time. They went along with the sound of a tinny piano playing in the parlor downstairs. ‘Mister, I met a man once when I was a kid.’ Huh. I guess neither one of our stories was very funny. Tell me, who was it you left me for? Was it Laszlo, or were there others in between? Or aren’t you the kind that tells?”

Now that’s about as close as Rick could get in those Hays Code years to calling Ilsa a whore. The tinny piano in particular was a sign of a whorehouse. It’s a brutal line, and Ilsa immediately leaves. This truly is Rick’s lowest point, where he lashes out hatefully at the person he loves the most.

And it all happens right at the beginning of act two. According to the gurus, it’s all wrong.

But it’s all right for CASABLANCA.

Which goes to show, no fixed formula is going to work for every film. CASABLANCA actually has most of the Save the Cat story beats. But not in the same order, and not in the same way. And certainly not on the page numbers prescribed in that guide. And that flexibility is an important thing for screenwriters to note.

Anyway, once that scene is over, the first part of act two is all about people finding out there is not going to be an easy way out of Casablanca. Laszlo finds out that only the letters of transit will do for him, and Rick won’t sell them. Jan and Annina, the young Bulgarian couple, also aren’t going to find an easy way out. We’ll talk more about them later. Meanwhile Rick goes about his business until he finally sees Ilsa in the market.

And finally, we get to the midpoint. Rick, sober now, talks to Ilsa in the market.

This is both an excellent and pivotal scene. Rick and Ilsa have a serious conversation as he tries to cozy up to her. But the lace salesman, trying to sell to Ilsa, provides a delightful counterpoint. It’s worth noting how it’s done, how the presence of this third person helps keep the scene from descending into melodrama.

Because there’s some pretty serious stuff going on. Because Rick learns why Ilsa abandoned him in Paris, and it shatters him. Because he finds out that the reason she left him wasn’t because of anything he did, or anything he failed to do. And it’s not because Ilsa lacked the courage to be with Rick. In fact, the reason that Ilsa left had absolutely nothing to do with Rick.

Ilsa ghosted Rick because, “Victor Laszlo is my husband. And was, even when you knew me in Paris.”

Yes, Ilsa left Rick when she found that her husband, Victor Laszlo, was still alive. And so she left Rick to be at the side of Victor Laszlo, a move that took far more courage than staying with Rick.

Rick is absolutely gutted. It’s a direct assault on Rick’s self-centered self image. Because he learns that the worst thing that ever happened to him had nothing to do with him. He is not even at the center of his own story.

Of course there’s an irony here. Because we’re watching CASABLANCA, and Rick is the center of the story. But you know what I mean.

Anyway, Rick’s entire world view is shattered. And he spends the next major sequence finding a new model of how to live in a world where he is not at the center of the story.

And that model is Annina, the Bulgarian girl who is willing to sleep with Louis in order to get her husband Jan out of Casablanca. She is willing to make this sacrifice for her husband, a sacrifice that will be completely unsung. She’s not looking for glory. She’s not doing it for her own sense of self. Instead she’s doing it for another.

And she inspires Rick with her selflessness.

We’re going to talk more about Annina shortly. Because I think she’s part of the brilliance of CASABLANCA. But for now, just note how her example inspires Rick to selflessness. And as a result, we see him do the first selfless thing we’ve seen him do in the entire movie: he has Emil the croupier let Jan win at roulette, thus giving Jan the money to bribe Louis for an exit visa. Annina will not have to sleep with Louis, and all Rick gave Jan the money. And gave it to him in a subtle way, a way in which he refuses any kind of applause.

It’s the first crack in Rick’s hard-guy façade.

Soon after that, we have the Marseillaise scene, where Laszlo leads the café in singing the Marseillaise and drowning out the Germans. But most importantly, it’s Rick who gives the bandleader the nod, tells him to play as Laszlo asks him.

Because now Rick takes a stand.

Oh, he’s not the guy leading the singing. But he gives his approval. The man who sticks his neck out for nobody has stuck his neck out. And, once again, done it from the shadows. Nobody but the bandleader could know that Rick was involved in the decision at all.

But the key point: Rick is moving away from self-centeredness.

Note how well this all comes together. The Marseillaise scene is one of the most stirring in CASABLANCA. It ramps up the conflict with Major Strasser and the Nazis. It shows Laszlo’s impact, why his fate is so critical. It gives us an iconic image of corrupt officialdom when Louis says, “I’m shocked, shocked to find that gambling is going on in here.” Which is, of course, one of the great lines in any film, and one that has entered the language.

But perhaps most importantly, this moment is a key milepost in Rick’s journey to being the selfless hero.

But he’s not quite there yet. There’s one other thing that has to happen first. He has to resolve things with Ilsa. And here I’m going to go out on a limb and share one of my interpretations of something that happens in CASABLANCA.

It all has to do with the scene where Ilsa comes to Rick’s room. She demands the letters of transit. Even pulls a gun on Rick. But he calls her bluff, says she should shoot him.

But she can’t do it. Instead, she declares, “The day you left, if you knew what I went through, if you knew how much I loved you, how much I still love you!” They embrace, kiss.

And fade to black.

When the lights come back up, the tension has gone. Rick and Ilsa are calm. Ilsa calmly tells her story. Rick is making plans.

So what exactly happened during that fade to black?

I think it’s pretty clear that they have sex.

Now, these were the days of the Hays code. Movies couldn’t show extra-marital sex. They certainly couldn’t show, couldn’t even hint at, adulterous sex. And after all, Ilsa is married, and not to Rick.

So it’s understandable that CASABLANCA couldn’t come right out and show them dropping into bed.

But I think it’s pretty clear that’s what happens. And from now until the end of the movie, Rick is calm and controlled and on his ultimate path to self-sacrifice for the greater good. As he later says, “We’ll always have Paris. We didn’t have, we lost it, until you came to Casablanca. We got it back last night.”

Yeah, Rick, we hear what you’re saying.

But however he got there, Rick has learned that the world doesn’t revolve around him, that other things are more important. He’s learned, “It doesn’t take much to see that the problems of three little people don’t amount to a hill of beans in this crazy world.” His character arc is complete, the theme has been stated, and all that remains to be done is to send Victor and Ilsa off on the plane, kill Major Strasser, and let Rick’s example inspire Louis, the most corrupt figure in the movie, to become his own best self.

Magnificent.

This is a superb structure. Rick, so self-absorbed, has his Rick-centric worldview shattered by Ilsa’s revelation about why she left him. He finds inspiration in the selfless act of a young Bulgarian woman. He gets his final push to the side of the angels from an act of love. And his selflessness in turn inspires the most corrupt self-centered character in the film to take a stand for goodness.

It’s a terrific character arc, a terrific story structure, and a wonderful theme that is perfectly in keeping with its time.

But there’s at least one more reason that I love CASABLANCA. And this one is a counter-argument to what I think is the most wrong-headed common bit of screenwriting “wisdom” that you’ll hear from a lot of people, the idea that all the characters in the film should be there to be part of the protagonist’s story.

Now there is some truth to this. You should know why every character is in your film.

But that doesn’t mean that every character should only be part of the protagonist’s story. And that’s a problem I see in a lot of movies these days – characters that don’t seem to have their own lives, their own purposes and goals. They start to feel like cardboard, like they’re only present in support of the story.

By contrast, in CASABLANCA there are dozens of fascinating characters that all have their own goals, backstories, and points of view. Even minor characters seem to have depths that we only barely glimpse.

Consider Carl, the waiter at Rick’s. He connects with the customers. He is in the underground. He delights in seeing Rick’s transformation. And at every moment, he seems like a complete well-rounded person who is not in this world just because Rick needs someone to deliver drinks.

Or take Yvonne. She’s the boozy barfly who Rick viciously rejects early on. Later she shows up on the arm of a German officer. But when Laszlo leads the bar in singing the Marseillaise, she finds her patriotism as she stands in tears singing. In three short appearances, she has an entire character arc, and one that incidentally reinforces the theme of how one person can inspire another. And reinforces the importance of Laszlo. If Laszlo can even inspire a lost cause like Yvonne to patriotism, he must have something special.

Casablanca is full of vivid characters that never interact with Rick at all. Think of the Pickpocket, so notable as he says, “I beg of you, Monsieur, watch yourself. Be on guard. This place is full of vultures, vultures everywhere, everywhere!” While, of course, being one of the vultures.

In fact, one of the things that I find notable in CASABLANCA is how many of the supporting characters could easily be the protagonist in their own films. I’d love to see the caper flick where Ugarte steals the letters of transit. Or the inspirational hero story of Victor Laszlo’s escape from the Germans. Or Yvonne’s story, expanded from that three-scene arc, from boozy barfly to patriot. The movie is full of vivid characters who could step forward to lead their own story.

But what’s the advantage of that? Don’t all those characters just distract from Rick’s story? Wouldn’t we be better off spending that time with Rick, Ilsa, Victor, and Louis?

No, I don’t think so. In particular, I think there are two major advantages to CASABLANCA’s approach.

First, the presence of all these people with all their individual stories makes the world feel so much more real. Which in turn makes Rick’s story feel more real. The world is not just about one protagonist leading his own story and everyone else just being a part of it. It’s about one story in a complex world full of stories.

I often find that the worlds of movies from the 40’s, movies like CASABLANCA, feel a lot more real than movies made today. Because the movies made today lack that broad sweep of humanity. They don’t feel like they are populated with real people, but rather with paper cutouts who are present only in service to the protagonist’s story. By contrast, the broad collection of characters in CASABLANCA, all of whom have their own lives and stories, many of whom never interact with Rick even indirectly, make this world feel much more authentic.

But there’s another major benefit to this broad cast, and that is in evidence in CASABLANCA. Because sometimes a background character will step up and be an important part of the story. And when that happens, it’s far more believable if she’s part of a wider story world.

CASABLANCA’s best example of this is Annina, the young Bulgarian girl. We see flashes of her and her husband Jan throughout the film. In one of the first scenes, before we even meet Rick, we see her staring longingly at the sky, hoping to be on the next flight to Lisbon. She appears in the police station, being told by an official that there’s nothing that can be done for them. Later there’s a flash of her and Jan being turned away by Ferrari who tells them that they should try to get help from Louis.

These are all short scenes, blink-and-you’ll-miss-it moments. They’re just enough to establish that Annina is there, another of the desperate refugees, a part of the scenery. Just two more faces in the crowd.

And then Annina steps out of that crowd to talk to Rick. To be the thing that inspires him, a model of selfless love. To be the light that leads him onto a better path.

If CASABLANCA didn’t have so many characters filling its spaces, if Jan and Annina were the only desperate people we saw, it would be immediately obvious that they are being set up to be significant. But because they are only two of many (the Amsterdam banker, the man paying a fortune to get out on boat, the woman selling her jewels, the man having his pocket picked), when Annina steps forward and takes center stage for her moment, it feels more organic. She feels like a person, not just a device.

I wish more modern movies would take this to heart. I wish they would exist in fully populated worlds where supporting characters aren’t just there as support. I think it would make for better movies.

Anyway, that’s CASABLANCA. As I said, I think this is the greatest screenplay ever written. Because I think its structure is terrific, Rick’s character arc is superb, the dialogue is as good as has ever been written, and the broad collection of supporting characters makes the world both fascinating and believable.

So what are my three lessons from CASABLANCA?

First, don’t be afraid to put lots of characters in your film. Don’t limit yourself to characters who will have a direct impact on the protagonist’s story. A broad cast of characters with their own goals and needs makes for a bigger more realistic world. And who knows, you never know which of those characters will become crucial.

Second, think carefully about your themes. And make your characters represent and reflect those themes.

CASABLANCA is about the need to put aside personal wants to work toward the greater good. Because that is what was desperately needed in 1942 when it was made. So Rick has to start out terribly self-centered. And he has to be led to a place where he can sacrifice the great love of his life for the greater good.

Third, use supporting characters to reinforce the themes and the protagonist’s character arc. Louis is if anything even more self-centered than Rick. But inspired by Rick, Louis also takes a stand, steps up and joins the side of the angels.

At a lesser level, Yvonne is clearly only interested in her own personal concerns. But she is inspired to patriotism, to something beyond her own selfish needs, through singing the Marseillaise.

These characters reflect and mirror Rick’s arc. Which reinforces the theme.

And that’s CASABLANCA. Now to a couple other things.

There’s nothing much to report about DOMICIDAL this month. We’re focusing on our social media presence and campaign, and we’re applying for grants and figuring out what terms we’ll offer investors. Lots of tedious producing work that needs to be done but isn’t that exciting.

But if you want to follow our social media, go to the DOMICIDAL website at http://domicidal-movie.com. It has links to all our social media. You can even sign up for our newsletter, which I promise we’ll be publishing soon. And which is another of those things I’m working on this month.

Links to that website, along with a link to the Storylanes analysis of CASABLANCA and the screenplay I used in this analysis are at http://storylanes.com. As well as a copy of the script of this episode.

Now as I mentioned, I’m planning on once again focusing this podcast on screenplay analysis. It’s a subject I find fascinating, and an exercise that I find incredibly educational. And I hope useful for you, the listener. Because I really do think this is the best way to become a better screenwriter. Well, this and writing screenplays, of course.

As of right now, my plan for the next episode is to do a two-fer. If I can find copies of the screenplays, I’m planning on analyzing THE SHOP AROUND THE CORNER, a 1940 romantic comedy, and YOU’VE GOT MAIL, the 1998 remake that moves the movie from a small curio shop in Budapest to online New York City. I absolutely love THE SHOP AROUND THE CORNER, and I find fascinating the ways that YOU’VE GOT MAIL is similar and the ways it differs. At points it’s an almost beat-by-beat remake. And yet somehow it loses much of the original’s charm and pathos. I think it will be fascinating to study why that is the case.

Meanwhile, check us out at storylanes.com. And subscribe on any of the regular podcast services so you won’t miss the next episode. Until then, this is Joe Dzikiewicz of the Storylanes podcast. Talk at you later!

[/et_pb_text][/et_pb_column] [/et_pb_row] [/et_pb_section]