This episode, we analyze DIE HARD, the great 80’s action thriller. Here’s the links:

And here’s the script of the episode.

Note: that’s the script: not the transcript. This is the script I used when recording the episode. Some changes may have occurred in recording and editing.

Hi, I’m Joe Dzikiewicz, and welcome to the Storylanes Podcast, the podcast where every week we do a deep dive into a movie or TV episode. And to go along with this analysis, every week I publish a graph of the story we’re covering on the storylanes.com website, a graph I produced while doing the analysis. You don’t need to look at that graph – the podcast is standalone. But if you’re interested in diving a little deeper, check it out at storylanes.com.

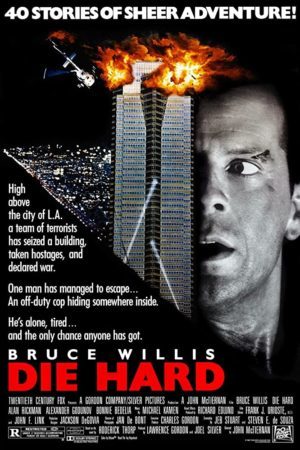

This week we’re covering Die Hard, the great eighties action thriller written by Jeb Stuart and Stephen de Souza based on the novel “Nothing Last Forever” by Roger Thorp, starring Bruce Willis and Alan Rickman and directed by John McTiernan.

Now I should mention: you shouldn’t listen to this podcast if you haven’t watched Die Hard. I’m not going to be telling its story, but I am going to be revealing a whole lot of spoilers. So it’s kind of the worst of all worlds: the movie will be spoiled, and you won’t understand what I’m talking about. So go watch the movie, okay? It’s a good one, I promise.

Die Hard is the story of John McClane, a New York cop who goes to Los Angeles to try to reconcile with his wife. That reconciliation is interrupted by a group of terrorists who crash the wife’s Christmas party, taking over her office building. John McClane takes down the terrorists one by one, complete with lots of gunfire and explosions, and at the end he defeats their nefarious plan, saves his wife, and rides off into the sunrise, reconciled with her and back in love again.

That’s the story of Die Hard.

Now let’s talk about why it’s so compelling.

The first reason, not surprisingly, is the characters. There are some excellent characters in here, staring with John McClane, the protagonist, played by Bruce Willis.

John McClane is tough and resourceful. But any action hero needs to be those things. Where he stands out is that he shows a surprising amount of vulnerability, both physical and emotional. This is not an Arnold Schwartzenneggar iron robot. John McClane makes mistakes. He’s not the best husband in the world. He struggles with the challenges that he faces. He shows self-doubt, like when he does nothing to stop the murder of Mr Takagi, the local head of the Nakatomi Corporation, a murder that he allows because he realizes that he can’t do anything, the terrorists have him too outnumbered and outgunned at that moment in the film. And to symbolize his vulnerability, he’s barefoot for most of this movie, something that becomes key when he has to run across a floor covered with broken glass.

It is these weaknesses that make him work so well as an action hero. The fact that he spends so much of the movie in obvious pain and at the end of his resources make him compelling, because they make us, the audience, worry for him.

So here’s screenwriting lesson number one: we don’t want our heroes to be perfect. We don’t want them to be so powerful that we never worry about them. Weaknesses and flaws can be the secret of a great hero, and the more they have to deal with, the better the story.

And you know what else makes John McClane so compelling? Hans Gruber, his opposition, played by the great Alan Rickman. Hans Gruber is one of the all-time great villains. And it’s interesting to see what kind of villain he is.

Some villains are the dark mirror of the hero, showing what the hero might be if he took a darker path, cut a few too many moral corners. But that’s not Hans Gruber. Hans is the opposite of John McClane. Where McClane is all-American, Hans Gruber is European. Where McClane is a regular guy, Gruber is cultured, with a whiff of the upper class. You can imagine running into McClane at your neighborhood bar having a beer. But you’d never find Hans Gruber there – he’d be spending his time at some fancy place sipping champagne and noshing on caviar. John McClane runs around in a grubby t-shirt while Hans Gruber is elegant in a tailored London suit. There’s no dark mirror here: this is a case where opposites attack.

There’s another screenwriting lesson. There’s lots of good ways to craft villains. But one is to have the villain be as different than the hero as possible. This works particularly well if you want a good old fashioned story of good guys vs bad guys. There’s no moral ambiguity in that approach, and no moral ambiguity in Die Hard. But it works quite well for this kind of story.

Another thing Hans has going for him is that he is brilliant. His plan is amazing, he is constantly catching little clues and knowing what they mean, and he outsmarts just about everyone in this movie except for McClane.

It’s worth taking a moment to look at some specific examples of Hans’s brilliance. So I’ve added a lane to the Storylanes Die Hard analysis, one labelled “Hans is Smart.” You can see moments in the script where Hans does something that indicates his brilliance. But let’s talk about some of them here.

When John McClane pulls the fire alarm to get the attention of the authorities, Hans knows to have his men call the emergency services and report a false alarm, thus neutralizing McClane’s attempt. Further, he knows that the floor where the alarm was set off will be a key clue in finding McClane, since whoever set off the alarm must have been on that floor.

When John McClane uses his CB radio to try to get the attention of the authorities, Hans realizes that McClane probably went to the roof to get the best reception, so he immediately directs his guys there to find McClane.

When McClane sets off the explosion that destroys the anti-tank gun, Hans knows that the police are not using artillery, the explosion must have been set off by McClane.

Over and over again Hans makes the most of the clues available to figure out what’s going on, showing us just how smart he is.

But there’s two things that I think really stand out. The first is the details of his plan. Hans Gruber has worked out every contingency and every eventuality. He not only knows that the FBI will cut off the power to the building, it’s a key part of his plan for breaking into the vault. He knows he can buy time by demanding the release of various terrorists around the world. He’s figured out how to get into the vault, how to counter the police and FBI, and how to get away with the money. In fact, he outsmarts everyone in this movie – everyone except John McClane.

The other moment that shows Hans’s brilliance is the moment when he meets John McClane while wandering around the building. He is at this moment completely at McClane’s mercy. But Hans doesn’t panic: he immediately pretends to be a hostage and puts on a completely convincing act, even using the name of a real hostage. His act is so convincing that we worry for McClane .

Of course, McClane has seen through the ruse. But that shows one of the big advantages of a brilliant Hans – it elevates John McClane. Because in order to defeat Hans Gruber, in order to outthink someone who is so brilliant, McClane must dig deep and show even greater intelligence and grit. This is a case where a great villain makes a great hero – we would not want to see John McClane up against some third-rater. Where’s the challenge in that? No, we want to see him pitted against the best, because only then will John be the best. Only then does he have to be the best.

And there’s another screenwriting tip. The better the villain, the better the hero. And therefore the better the story.

The next character to look at is John’s wife, Holly Genaro McClane. Holly has grit and resourcefulness. She’ll confront Hans if it’s required to take care of her people, as when she asks that her pregnant secretary be allowed a couch to sit on. She’ll even talk back to him, like the moment when he asks what idiot put her in charge and she responds “You did. You murdered my boss.” She even shows contempt for Hans when she finds out that his motivation all along was simple theft even though he is armed and she is not. And finally she lands a solid punch on the newscaster who outed her on TV and put her life in jeopardy.

But there are some problematic things about how Holly is presented in this film. Ah, the 1980’s, when Ronald Reagan was in the White House and America was rediscovering its traditional roots! Holly’s feminist desire to have her own career independent of McClane is presented as a problem. And not just for John – the watch that is the symbol of her success in her job almost kills her when Hans catches onto it before his final fall. It’s only when she removes the watch that she can be rescued.

And the fact that she uses her maiden name in Los Angeles is an obstacle to her reconciliation with John. When she renounces at the end of the movie and goes back to being Holly McClane, it’s the final sign that she and John are now reconciled.

But things aren’t as problematic as they might sound. Because John comes around to the idea that Holly deserves her shot, that he should support her. He reveals this when he’s at his low point, and in what he thinks may be his final message to the world, he apologizes to her. This shows his growth, but it also shows that Die Hard is okay with Holly having a career.

But here’s a little something that I noticed, and I’m not sure exactly what it means. When Holly uses her maiden name of Holly Gennaro, her initials are “HG.” The same initials as Hans Gruber. So is this a sign that when Holly has abandoned her McClane-ness, she’s gone a little to the dark side? I certainly think it’s saying that Holly Gennaro is part of John’s opposition in this movie, while Holly McClane is John’s ally.

The next major character to examine is Al Powell, the nearest thing to being John McClane’s buddy or sidekick throughout his ordeal. Al’s a desk-jockey cop meant for better things. He serves as our point of view on what the cops are doing during the siege. He’s also John’s ally on the outside, giving John both counsel and emotional support. And he is a positive figure throughout. Someone who has to deal with his own self-doubts, but manages to overcome them to do the right thing at the end.

It’s worth noting that all four of these characters have well-defined character arcs. John McClane goes through the fire to discover that his wife getting a job isn’t the end of the world. Hans Gruber’s travels many of the steps of a Joseph Campbell-style hero’s journey, something I’ll discuss later. Holly discovers that she still wants to be Mrs McClane. And Al Powell, who benched himself as a cop after unintentionally shooting a kid, gets his nerve back when he guns down Karl the terrorist in the last scene of the film.

So another screenwriting lesson: your protagonist is not the only character who deserves an arc. More character arcs make for a richer story, and any character without an arc is going to be two-dimensional at best.

Once we get past these major characters, we have several vivid minor characters. Characters like Harry Ellis, Holly’s boss at Nakatomi, who is a rival for Holly’s affection, at least in his own mind. And who is such a jerk that when Hans shoots him in the head, we’re tempted to cheer. Or laugh, at the very least.

There’s Argyle, John’s limo driver. A fun-loving kid who parties through most of the film and takes down one of the terrorists at the end. The wimpiest of the terrorists, to be sure. But hey, not bad for a limo driver!

Then there’s the terrorists. And they’re a real strength of the movie.

A film like this needs a bunch of goons for the hero to take down. But it elevates the film to have those goons stand out as individuals, as they do here.

There’s Karl, the raging psychopath, who wants nothing more than to get revenge on McClane for killing his brother. He even defies Hans to increase his chance of killing McClane.

He also has his own character arc: a typical revenge story, though one that ends badly for him. He serves as McClane’s primary physical opponent, and the fight between the two of them is one of the more notable and extended action sequences of the film.

There’s Theo, the smartass tech wizard of the terrorist team, who sits at the center of the computer controls working on opening the vault while keeping an eye on the security cameras and making smartass comments over the radio.

And there’s other moments when the terrorists appear as individuals, like when Uli takes a moment while getting ready for a gun fight to steal a candy bar. All of these things make these guys more than just a gang of off-the-shelf goons, which elevates the film.

And we should congratulate Hans for being an equal opportunity employer. The terrorist gang includes Europeans and Americans, whites, blacks, and Asians. There’s no women, but hey, it was the eighties.

And quite aside from joking, the ethnic diversity of the terrorists help make them stand out. Which is a good thing.

Because in a movie like this, you absolutely need a bunch of goons for the hero to kill. That’s the name of the game. But in Die Hard, we can tell the difference between these characters, both because of their personalities, but also because of their diverse ethnicities.

So there’s another good tip for screenwriters. And casting directors as well, because the script doesn’t give the ethnicities for all these guys, though it does give them defining personality traits.

There’s another group in this movie that could blend together in a lesser film but who stand out individually. I like to call these the Official Dicks. Because in Die Hard, almost every character with official status stands out as a dick. And the higher up the chain you go, the more dickish: there’s a hierarchy of dicks in this movie.

At the bottom of that hierarchy is the supervisor of the emergency services dispatchers, the one who, when contacted by McClane on the CB, give him a hard time. But at least when she hears gunfire, she acknowledges that there might be a problem and sends Al Powell to check it out.

Moving a little higher, we have Dwane Robertson, the police chief who leads all the L.A. cops on site. He’s an absolute dick who is wrong about almost everything, who ignores the advice of John McClane, and who only manages to cause more problems for McClane while barely being an obstacle for Hans.

There’s Richard Thornberg, the TV news reporter who latches onto the story of the terrorist takeover. He’s such a dick that he almost gets Holly killed by revealing her relationship to McClane on TV. And note his name? Richard, which means his nickname is Dick.

And then we get to the top of the hierarchy of dicks and we meet the FBI agents. They’re such dicks that even Dwane Robertson realizes that they are dicks. They’re such dicks that they’re both named Johnson!

These guys only really care about getting their jollies in this fight. It doesn’t bother them that they might kill 20% of the hostages if they can gun down the terrorists. They even shoot at John McClane.

And so, as seems totally just, the Johnsons are blown up when Hans sets off the explosives on the roof of the Nakatomi plaza. And good riddance to them.

So what purpose do these official dicks have in Die Hard? I think there’s two primary purposes.

First, they provide a foil for Hans Gruber. To some extent, the official dicks serve for Hans what the terrorists serve for McClane. They are cannon fodder for Hans to take down, showing off his prowess before moving on to the final confrontation.

And Hans deals with them quite effectively, and the way he so effectively brushes off their efforts provide solid evidence for Hans’s intelligence. And in turn elevate the magnitude of McClane’s accomplishment in defeating Hans. After all, John McClane single-handedly defeats the man who defeats the LA Police and the FBI. Pretty impressive, no?

The other thing the official dicks do is give John McClane another set of obstacles. McClane not only has to defeat a building full of terrorists, he also has to overcome all those official dicks. A significant extra source of conflict is a good thing in any story, and all those guys provide plenty of conflict.

And if the officials were of any use, it would leave McClane less to do. It’s hard to be a lone wolf hero when you’ve got the backing of competent government forces. So for a story like Die Hard to work, there has to be some reason that the officials aren’t handling the problem. In this case, the reason is, they’re dicks.

There is one other thing worth noting here. Aside from Al Powell, every official in Die Hard only provides problems for McClane. Whether they are the police, the FBI, or the media, all these authority figures are problems, not solutions. Which is another sign that this is the 80s, when Ronald Reagan liked to say that government wasn’t the solution, it was the problem. Die Hard is squarely in Reagan’s corner.

So, screenwriting lessons: it’s always good to have more than one source of conflict, and there has to be some reason why the hero has to solve the problem and can’t just rely on others. Sure, you could come up with some reason why the hero can’t call the cops. But how much more satisfying is it when the hero calls the cops and they turn out to be part of the problem, not part of the solution?

So that’s our cast of characters. A particularly strong set of characters, led by a great hero and a great villain, and including an engaging set of supporting characters.

So now let’s take a look at what all these characters do and dive into the story structure.

From a high level, the structure of Die Hard is a pretty standard action film structure. There’s an opening act that establishes the hero, the setting, and introduces a challenge. Then there’s a series of action sequences that escalate in both meaning and scope, leading finally to a confrontation between the hero and the villain in which the hero emerges victorious and wins the girl.

On that level, there’s not much to distinguish this from many other action films. It’s well-executed, to be sure. But the basic flow is fairly standard.

So what makes Die Hard stand out?

Well, I think there’s a few things.

First, there is John McClane’s motivation. John McClane’s goal from the start of the film is to reconcile with his wife. He comes to Los Angeles for the express purpose of reconciliation. And that’s behind all his actions.

This is a relatable want, wanting to fix a relationship that’s gone bad. This is an easy thing for an audience to empathize with. We’ve all been there. Seeing McClane pursue this simple need puts us entirely in his corner.

And keeps us with him throughout the film. Because McClane’s motivation, even through all the fights with the terrorists, is to reconcile with Holly. The purpose that the terrorists play is to be an obstacle to that reconciliation. After all, John can’t reconcile with Holly when she is being held hostage. He must free her before they can get together again.

McClane’s primary motivation, then, is not defeating Hans and stopping his plans. And frankly, we the audience don’t care about stopping Hans’s plan. What do we care if Hans gets away with the bearer bonds? It’s not our money, and the film never tries to give us a reason to care.

But it gives us a reason to care that John gets back with Holly. And that is enough.

So lesson to the screenwriter: make it personal and give the audience a reason to care.

There’s another character whose wants drive this film, maybe even more than John McClane’s wants drive the film, and that is Hans Gruber. Hans wants the 640 million dollars in bearer bonds that is sitting in Nakatomi’s vault. Now Hans is the villain, so we don’t have to be on board with his desire. But we should be able to understand it. A villain who is evil just for the sake of being evil isn’t as satisfying as one who we can understand, and even empathize with his goals. And I don’t know about you, but I get why Hans wants all that money. I completely get why he’d go to all this effort, come up with this masterful plan, put together this amazing team. All so he can get his hands on all that money.

Of course, John McClane ends up being Hans’s obstacle. He’s the only reason Hans doesn’t end up with the money.

So we have two characters, a protagonist and an antagonist, each with strong wants, each the obstacle to the other. And so we have a movie.

And because we don’t really care if Hans accomplishes his goal, but we do care if John accomplishes his, we’ve now got a rooting interest and we’re on McClane’s side.

Now note: you can imagine this playing out in such a way that both could get what they want. If early on, Hans was a little less blood-thirsty, McClane a little less concerned about the other hostages, we could imagine Hans offering to let Holly go if John leaves him alone. And some versions of John might say yes, leading to a win-win situation.

That wouldn’t be as satisfying as all those lovely explosions, though. So it’s not going to happen.

But screenwriting lesson: set up characters with strong believable wants that are in conflict with each other, and see how they play out. But don’t allow an easy reconciliation!

And one more thing to note. You could imagine a version of this where we are on Hans’s side. Make him less willing to kill innocents, give us a reason to want him to have the money. Perhaps make Nakatomi evil. Perhaps Hans will use the money to house the homeless. Let Hans win in the end and we can be happy with this fun little heist film. There’s many versions of this. It’s “Inside Man.” It’s “Oceans 11.”

So the details matter so much. Which is, of course, another great screenwriting lesson.

But Die Hard doesn’t give us a reason to want Hans to have the money, and it does make him a villain, so willing to kill people to accomplish his goals. So this is Die Hard and not Oceans 11.

A little earlier I mentioned the escalating action sequences. Now let’s talk about those. Because I find the details of those sequences and John McClane’s immediate goals in them to be fascinating.

McClane has the overriding goal of reconciling with his wife, and when the terrorists arrive that turns into the goal of defeating the terrorists so he can rescue Holly and then reconcile with her. But how’s he going to do that?

Imagine yourself in this situation. You’ve gone to a party with a loved one and terrorists take over the building. You escape, but your loved one is captured. What would you do?

I don’t even mean, what would you do if you were a tough New York cop capable of beating up terrorists. I mean, what would you do if you were you? Running loose in a building where terrorists have captured someone you love, and you’re the only one who knows they’re there.

I’d try to call the cops. Really, it seems like the most sensible thing to do.

So what does John McClane do?

He tries to call the cops.

And this is wonderful. Because it makes so much sense. McClane doesn’t try to single-handedly take on a whole host of terrorists. He doesn’t go around setting traps, or try to launch a rescue raid, or anything like that. No, his first thought is pretty much the same first thought that most sensible people would have.

Get help. Get backup. Call the cops.

As an audience member, I’m completely on board with this plan. So much that I never even think twice about it. And I find this to be another strength of the movie – there is never an instant in Die Hard when I wonder why McClane takes the steps he takes. And that makes Die Hard stand out. I spend a lot of time in a lot of movies second guessing the heroes. But not in Die Hard.

So, screenwriting lesson: your characters in this kind of movie are going to do big, dramatic actions that are beyond the capability of most audience members. But how wonderful if their instincts are the same as mine, it they’re not doing something vastly different than I’d do, but doing what I’d do at a different scale. How great is that!

Of course, getting the attention of the police isn’t easy. You don’t want anything to be easy for the hero of a movie like this. The terrorists have shut off the phones to the building and McClane doesn’t have a cell phone. So he has to spend the next thirty pages of the script getting the attention of the police. (And for those not used to reading screenplays, one page is roughly one minute. So figure McClane takes about half an hour before the police arrives.)

He does all kinds of things to try to get official attention. He tries pulling the fire alarm, but Hans neutralizes it. He calls the emergency dispatchers, but they are official dicks and so only grudgingly send someone to investigate. And when Al Powell arrives, at first he is fooled into thinking all is calm, so McClane has to drop a body from on high onto his car to let him know something’s going on.

And, of course, throughout all of this McClane has to avoid being caught by terrorists, and he kills several of them.

So put it all together, and it takes thirty action-packed pages before McClane manages to summon the police. Which, after the 22 pages of the first act, brings us to page 52 and the next big section.

But the police are here, so McClane can relax and let them handle things. Right?

Wrong. Because what are the police? They are official dicks. So they are completely useless. Less than useless, really – the police keep getting into trouble, and McClane has to get them out of it.

This is another fun little detail that I had never noticed before. After spending 30 pages summoning the police, John spends the next 60 pages getting them out of his hair. And in those pages, McClane has to deal with two major screwups by the official dicks.

First the LA police under Dwane Robertson send a SWAT team and armored car to attempt a hostage rescue.

Of course Hans and his men are ready for this. They not only have many machine guns. They have an anti-tank gun. The police don’t stand a chance. McClane tries to tell them they don’t stand a chance, but of course Dwane Robertson blows him off, because he’s a dick. And the only thing that keeps this failure from being an utter disaster is when McClane drops a bomb on the anti-tank gunners, blowing out a chunk of the third floor of the Nakatomi building and two terrorists.

So McClane saves the police from their own stupidity. But there’s more stupidity to come, because the FBI has arrived.

First the FBI turns off the power to the building, which is exactly what Hans wants, because that is the key to opening the final lock on the vault and letting Hans have his money.

Then the FBI is going to launch an aerial assault on the building. They don’t even care that this will probably kill some hostages. Because they’re dicks. Of course, Hans has planned for this too, and has set bombs on the roof. In the chaos that will follow the explosion, Hans and his guys will escape.

A lot of hostages will die. But Hans cares even less about that than the FBI do.

But McClane cares. His wife is one of the hostages, and he doesn’t want her to get blown up. It’s kind of hard to reconcile with your wife when she’s blown to bits. So McClane goes up and scares the hostages off the roof.

Of course, the FBI tries to shoot him. And he almost gets caught in the explosion. Which is all okay, because the FBI misses and John escapes and the FBI gets blown up. Which gets them out of McClane’s hair.

So here we are, on page 111 of the screenplay, and the official dicks have been causing problems for the last 60 pages. But finally they are all neutralized. The police are neutralized because after their failure the FBI took over, and the FBI are neutralized because they all got blown up. And it’s hard to be more neutralized than blown up.

And with the official dicks all out of the way, McClane can at last go confront Hans one-on-one, the final confrontation that we’ve been waiting for.

But do note the nice little irony here. In this section of the film, a fully sixty pages of script and thus roughly an hour of screen-time, McClane’s primary obstacle is the official dicks doing stupid and dickish things. And his major accomplishment for this hour is to get the official dicks off the playing board. Only then can McClane go and deal directly with Hans. He spent thirty pages summoning the police, then sixty pages making them go away. Pretty neat, huh?

Oh sure, other things happen in that 60 pages. McClane’s meeting with Hans is in there, as is his epic battle with Karl. Hans manages to open the vault and get the bearer bonds, and Hans discovers he has the ideal hostage in Holly.

But at the large scale, the most important thing that happens in that 60 pages is that the official dicks are eliminated as an obstacle.

I love stories where the solution to one problem turns out to be the cause of the next problem. Die Hard does this really well. McClane works so damned hard to summon the police, only to find that the police are a giant problem. And now he has to work twice as hard and twice as long neutralizing them. And the FBI end up neutralized, because they’re blown up in a helicopter. And the Police are neutralized, because they’ve been so effectively neutered that they’re not even trying any more.

This is a great way to write a screenplay. So screenwriting lesson: consider having your hero’s solution cause future problems.

Now clearly, you don’t have to do that in every screenplay. The key point here is that McClane has a minor success early in the movie, in this case, contacting the police. So the audience gets the reward of seeing the hero succeed. But there’s still another hour to go, so you need a whole lot more conflict. So add another big obstacle. Conflict and obstacles are great, are at the heart of screenwriting. So adding a new conflict-ridden obstacle halfway through the movie is a great idea.

So, Die Hard’s got great characters and a cool story structure. Now let’s look at some craft things that make this such an interesting movie.

First off, Die Hard does something truly interesting in the way it creates its action scenes.

In a movie, a scene is typically characters interacting in one location in one period of time showing some event.

But Die Hard does things differently. In Die Hard, you might have a number of characters in different physical locations interacting at one time around a single action. So the concept of a scene is broken up.

Let me give you an example of how this works.

Starting at page 62 of the screenplay, Dwane Robertson, the police chief, orders the SWAT team to go into the building. This is a single action that takes place: the SWAT team’s attack on the building. And it occurs at a specific moment in time: the moment when the team goes in.

But we see that action from the point of view of different groups of characters in different locations around the building. We see Dwane Robertson order in the team. Then we see John McClane on an upper story of the building realizing that something is happening and watching the action below. He goes on the CB radio and talks to Al Powell about the attack, and we see Powell. Then we see Hans Gruber in an office of the building go on the CB and give orders to his men on how to respond. We then jump to several groups of terrorists at various locations get ready for action. We’re now with the SWAT team coming up. Then back to Dwane Robertson order the men in. Then there’s an establishing shot of security cameras, setting up the next shot, of Theo in the computer room who sees that attack coming on the security cameras. And so on and so on and so on.

There is only one event: the attack by the SWAT team and the response by McClane and the terrorists, but we see it from a total of nine different points of view. We see it from the points of view of John, Hans, Robertson and Powell, the SWAT team, two groups of terrorists, Theo in the computer room, and the hostages reacting to the sounds of explosion. It’s not the same as an omniscient point of view, because at any time we’re seeing things from one character’s point of view. But it is a broad tapestry of multiple points of view.

Let’s look at the numbers. The sequence containing the SWAT team and armored car attacks takes 9 pages of screenplay, so roughly 9 minutes of movie. That nine minutes includes 33 individual scenes for an average scene length of just 16 seconds per scene. That’s a lot of short scenes!

So what’s the benefit of all these scenes? It shows us all the dimensions of the action. We’re not limited to a single point of view. And it makes all the characters stand out more. We know Hans Gruber a lot better because we see what he’s doing at these moments of tension, where another film might limit our view to just what the hero sees. It lets us show all the most interesting parts of the action without having to contrive a way to have the hero be at all those key points, which is a much more realistic way of doing things. And by seeing how these actions affect all these characters, it broadens the impact of the action. Terrific stuff.

For just a moment, let me put on my filmmaker’s hat, because when I’m not analyzing films I’m often making them. The logistics challenge of making a film this way is incredibly impressive.

The thing that takes up the most time on a film set isn’t filming the scene. It’s preparing to film a scene. Getting the set ready, setting up lighting, getting the actors in costume and makeup, getting the cameras in place – all of these take time. When I’m making a film, I assume it’s going to take roughly an hour per scene just to set up – and that’s in no-budget small productions. Large-scale Hollywood films can take even longer to set up a scene. It usually takes a lot longer setting up the scene than filming it, so if you want to be the most efficient, you have a few long scenes.

Clearly this isn’t the Die Hard way. Admittedly, some of those scenes are set in the same place with the same characters. But there’s still a whole lot of setups in that one sequence. And this isn’t the only such sequence in the movie.

Just thinking about it, my hat’s off to Benjamin Rosenberg, the assistant director of Die Hard, because it’s the assistant director’s job to keep track of the shots on set. And the organizational challenge of making a film like this is impressive indeed. So well done Benjamin Rosenberg and his team!

But let’s get back to the writing. There’s one particular craft aspect to the writing that I want to call out. Seeing action from so many points of view is challenging for an audience to track. But you never get lost here. How do they pull that off?

One of the key ways is that the transitions between scenes are all well designed. Typically, there is some specific element that takes us from scene to scene to scene.

One way they manage scene transitions is through communications. Several of our groups have CB radios, and we often see one person initiate a call and another receive it. So we see Hans Gruber gives orders to his man over the radio, and the scene transitions from Hans to the men receiving the call. Or John McClane talks to Al Powell and we see a transition. Or John to Hans. Or maybe we’ll see someone just listening to the CB and not talk – the news reporters snoop like this, as does Argyle in his limo.

The TV reporters provide another type of communications. We’ll see the TV reporters film something, then see someone else watching it. The watchers at various times include the terrorists, Argyle, and the hostages.

Or there will be some big event that can be seen from different locations. Most notably there are the explosions – whenever we have an explosion, we typically jump between multiple groups causing the explosion, or seeing it, or hearing it, or just being blown up. In fact, the last seven scenes in the SWAT team sequence are all different points of view on the explosion, including John McClane dropping the bomb, the anti-tank gun team being blown up, the police seeing the explosion from outside, a view from the garage of people hearing the explosion, the news crew getting the explosion on film, Hans hearing it, and finally Holly and the hostages hearing it. All of these are tied together by the explosion.

Now not all of these cuts are motivated. But usually, the first time we cut to a new group in a sequence is motivated. And once the connection is established between the groups, we can jump back to that group without as strong a motivation. So once we’ve established that there is a group of terrorists in one part of the building during an event, we can cut back to those terrorists at various times in the firefight.

The lesson here is that if you are going to use this type of tapestry of points of view, make sure you tie them together in a way that will keep the audience from being lost. Because losing the audience like this is a real risk.

But all of this is something that I think makes Die Hard so special. I can think of other films that give us multiple points of view during a large action. But there aren’t many that do it so well or show us so many points of view. Usually we jump between multiple protagonists. But here, we jump from protagonist to antagonist to police to terrorists to observers, so you end up seeing how everyone involved sees a bit of action. And it’s done so well that it doesn’t call attention to itself. Well done Die Hard!

So screenwriter note: this is a great way to tell a story. But this is most definitely a varsity-level technique – don’t do this unless you know you can get it right. And realize that if you do things the Die Hard way, even if you get the script right it’s going to make the film much harder and more expensive to shoot.

Note that in the Storylanes analysis, I’ve added a lane that I call super-scenes. The super-scenes identify scenes that span multiple traditional scenes across different locations. I’ve also added a lane that identifies the transitions between scenes within a super-scene. You can look at that and see many examples, not just the one I discussed here.

BREAK

Now we’ve look at the plot, so let’s do a quick run through the subplots, each of which has its own lane in the Storylanes analysis. And as you’re listening to these, consider how they affect John McClane and his quest to reconcile with Holly. Because every plot listed here ends up involved in that main goal, either as an obstacle or as something that helps John.

We’ve already talked about the primary action line. For the sake of argument, let’s call that the main plot. It’s pretty obvious how it serves as an obstacle to John’s reconciliation, so we can skip past it to the other subplots.

The first of these is the relationship between John and Holly. This is what brings John to LA. It starts with the first shot of the film, of his plane landing. It goes to the last shot, his riding into the sunset. It includes John learning that Holly has gone back to her maiden name, the argument they have over that, Holly defending what John’s doing to Harry Ellis, John’s regrets over not respecting Holly’s accomplishments in her new career, and finally, the last shot of the film, when Holly introduces herself as Holly McClane and the two go riding off in the limo into a new Christmas sunrise.

Now an argument can be made that the reconciliation plot is the main plot. After all, in includes the hero’s primary want, and it covers the start and end of the film. So label it as you wish, but this is an interesting way of looking at things.

I suppose the lesson here is that a film can be complicated, and the distinction between the primary plot and a subplot is not always clear-cut.

The next big subplot that I’d identify is Hans Gruber trying to steal the bonds. Because this brings the terrorists to the Nakatomi building, it motivates John’s major obstacle, the terrorists. The major plot points here are Hans trying to get Mr Takagi to give him the password, which fails. The constant return to Theo trying to break into the vault as the locks drop, one by one. The opening of the vault when the FBI turns off the building’s power. And then John McClane defeating Hans. And finally, at the end of the movie, we see the bonds scattered to the winds, showing that this plot is completely unimportant in the end. Really, once Hans is dead, nobody cares what happens to the bonds.

Next we have Al Powell’s proving himself. This is one that gives McClane support. Some of the key milestones are the various times we see Al Powell being a decent guy and offering John support. Then Al tells McClane why he is not a street cop – he killed a kid unintentionally and cannot fire his gun any more. And then we see Powell recover his manhood when he guns down Karl in the last scene of the movie, able to draw his gun once more, and thus removing the last obstacle to John and Holly’s reconciliation. After this, we don’t actually see Powell return to the street, but we know he does.

And Al gunning down Karl is the resolution of another major subplot: Karl’s Revenge. The inciting incident of this plot is John McClane killing Tony, Karl’s brother. Karl discovers it and swears revenge. This leads to a lot of moments of Karl hunting for McClane, and to the grand epic battle between Karl and John, a fight that spans several scenes and is one of the action peaks of the movie. McClane wins, but Karl returns in the last scene, to be gunned down by Al Powell. But clearly, if Karl won, if he killed McClane, that would serve as a pretty big obstacle to John’s reconciliation. Thus, another obstacle plot.

Then there are the authorities vs Hans. This starts when the police arrive. It goes through two of the major action sequences of the film: the raid of the SWAT team and the FBI’s helicopter assault of the building. It also includes the FBI turning off the power to the building. And because McClane finds himself in this middle of this fight, it’s another obstacle to reconciliation.

There’s Argyle’s big night, a subplot used mostly for comic relief. Argyle picks up McClane, hangs around in the limo in the garage throughout the siege, takes down Theo as he tries to escape, and then drives the McClanes away at the end, thus assisting with the reconciliation.

There’s the newscasters covering the story. This starts when Richard Thornberg hears on the police scanner that something’s happening at Nakatomi, it covers snippets of news coverage and attempts to get news coverage. It includes Thornberg’s interview with the McClane children and the subsequent outing of Holly as John’s wife, and it ends when Holly punches Thornberg as she leaves the building. This one provides some comic relief – there’s a lot of humor at the expense of stupid newscasters. But the revelation of Holly’s identity to Hans provides a major obstacle to the reconciliation plot by leading to her being singled out among the hostages.

So screenwriting lesson here. Note how Die Hard introduces all of these subplots, then ties them back into the main plot, providing either obstacles or support to the hero’s achieving his goals. But all these subplots, in addition to upping the stakes and adding to the opposition, provide additional layers of depth to the story. It’s well done, and as a writer it’s worth examining how these affect the main plot.

So those are the subplots. Now let’s take a look at the theme of this movie.

I wrestled with the question. Nothing really sticks out to me. The best I can settle on is, “Don’t be a dick.”

We see that play out in many ways. At the beginning, John McClane blows his stack when he learns that Holly is using her maiden name. He’s kind of a dick, and this complicates his reconciliation with her. Later in the film, at his low point, he asks Powell to apologize to Holly for him. In that scene, McClane renounces his dickishness, having learned from his ordeal to keep an eye on the important things. This removes dickishness as a barrier to John’s reconciliation, and so when they are finally together they can truly be together.

But “Don’t be a dick” applies to other characters as well. It applies to Hans. If Hans weren’t so willing to kill people in order to steal the bonds, if Hans weren’t being such a dick about it, we might be on his side. If he hadn’t taken Holly as a hostage, McClane might not care about the theft. And then Hans would get away with all that money. But Hans is a dick, and that keeps him from achieving his goals.

There are all those official dicks, who fail at their attempts to defeat Hans because they won’t listen to McClane. Instead they insist on being dicks. This culminates in the explosion that blows up a couple of Johnsons. They shouldn’t have been dicks.

There’s Richard Thornberg, the news reporter. He does better than most of the dicks in this film. After all, he does get his story. But he also gets punched by Holly, which the movie presents as a suitable punishment for his dickishness.

So, don’t be a dick, guys. Okay?

There is another possible theme here. There’s definitely a class divide in Die Hard. John McClane is a working-class guy, a street cop. Al Powell, his buddy, is also a street cop. Argyle, another good guy, is just a limo driver.

But Hans is refined and cultured. And the official dicks are mostly guys in suits. Harry Ellis is another dick in a suit.

Holly, of course, is striving to join the ranks of the upper class. But that’s presented as an obstacle to her reconciliation with John, and it’s only when she abandons the trappings of being upper class, when she loses that Rolex watch that symbolizes her job, only then can she be rescued and can the reconciliation take place.

So another theme: working class types are all decent salt-of-the-earth types, and the upper class are all dicks.

And now, in the homestretch, for the screenwriting geeks in the audience. Let’s look at what some standard screenwriting models tell us about Die Hard. And what Die Hard tells about those screenwriting models.

First is traditional Three Act structure, as introduced by Syd Field and since fine-tuned by others.

In Three Act Structure, you have Act One, which sets everything up. At some point, there’s an inciting incident, which starts the action of the film. Then there is Act Two, where the action largely happens, with escalating conflicts that the hero must navigate. Halfway through Act Two is the midpoint crisis, where the hero has a moment of triumph or failure and things change from the fun-and-games of the first half of Act Two to the more serious back half. Then there is the push into act three where the protagonist commits to action, and in Act Three you have the climactic event and the final resolution.

So how does this play in Die Hard?

Three act structure largely works here. There’s a clear first act, which covers the time from when John McClane lands at the airport until the moment when the terrorists have taken over the building and McClane escapes from them into the empty upper floors.

The inciting incident is when the terrorists arrive, the moment that kicks off the story of the film.

And on to act two, where things get a little more complicated.

Act two covers all the time when McClane is dealing with the police in a series of escalating conflicts.

But I think you could make an argument for either of two midpoints. The first would be when McClane has successfully summoned the police and they have arrived, which occurs on page 52. We’ve had a fair bit of fun, now things start to get a little more serious, as the police order in the SWAT team and McClane has to scramble to keep it from being a disaster.

But another possible midpoint is the big explosion when McClane drops the bomb on the anti-tank crew, at the end of the police attack sequence. Here also things start getting a whole lot more serious, with the FBI’s shenanigans and the big fight with Karl coming later. And this one occurs at page 70.

So we have possible midpoints at page 52 or page 70 in a 118 page script. One a little early, one a little late. Pick your poison.

But the subtext here is that I don’t think there’s one clear midpoint, in the sense of a turning point where things suddenly become more serious. To this extent, I think Die Hard doesn’t match the traditional three act model.

Similarly, I have some trouble pinpointing the turn into act three. Here I also have a couple choices.

One is on page 90, when McClane, who is now in tough shape, gets on the CB and asks Al Powell to apologize to Holly for him. This is certainly McClane’s low point in the film. He doesn’t think he’s going to survive, and it humbles him. But he then gets up and gets back to work, doubles-down and is ready to face his biggest challenges: the epic fight with Karl, keeping the FBI from killing him, and the final showdown with Hans.

Another possibility turn into act three is on page 111. McClane has dealt with Karl, he’s dealt with the FBI. Now he has to go and confront Hans, his final challenge.

Page 90 would be just about right for a turn into act three, leaving us with a 28 page act three. Page 111 would certainly be late, leaving only seven pages for act three.

But again, I don’t think the answer is clear. You could declare either of these to be the turn into act three and thus impose three act structure on Die Hard. But I don’t think it really fits.

And I don’t think it suffers from its failure to fit. So screenwriting lesson here: don’t get bogged down in a specific formula. Do what’s right for the story, and let others try to figure out how it fits some framework.

I think the same lesson applies if you try to look at Die Hard through the lens of Blake Snyder’s “Save the Cat.” Snyder starts with three act structure but then goes beyond to identify fifteen specific beats that all screenplays should have, and Snyder even goes so far as to specify on which page each beat should occur.

Several of Snyder’s beats are present here. But not all. For example, Snyder has a beat he calls the Debate, where the protagonist considers whether or not to act on the inciting incident. But John McClane never really questions whether he should do something about the terrorists. When they show up, he’s off and running.

And almost none of the beats are on the pages that Snyder specifies. (Though I have to wonder how serious Snyder was about the page numbers, given how absurd that sounds.) And in my opinion, the movie certainly doesn’t suffer from not following Snyder’s formula.

So the lesson here is the same as it was for three-act structure: don’t get too wedded to any formula. The story is more important than the formula, and practice more important than theory.

Not surprising, the same thing applies when looking at things from a Hero’s Journey perspective. The hero’s journey model was developed by Joseph Campbell, a literature professor who examined many traditional myths and found that they had a similar structure. It was popularized when Star Wars came out and George Lucas embraced the hero’s journey model.

As with Save the Cat, Die Hard has some hero’s journey beats. But not all. When McClane receives the call to adventure, which is what the hero’s journey calls the inciting incident, he never refuses it, one of the hero’s journey beats. He never finds a mentor, another beat. And several of the other beats don’t apply. So hero’s journey is only so-so as a guide to McClane’s story.

What I do find interesting here is that the hero’s journey can be applied to Hans Gruber’s arc.

Not the early beats of the hero’s journey. When Hans appears in the film, he’s already fully committed. He’s already heard the call of adventure and is already crossing the first threshold, a step in the hero’s journey when the hero jumps into the adventure, something that typically happens at the end of act one of a film.

But from there on, Hans follows the hero’s journey fairly closely. He faces a series of tests and enemies. He nears his goal when he is told that there is only one lock to go. Then he faces his ordeal, in this case the final lock on the vault, the one that is only opened when the FBI turns out the power. And then he gets his reward when the vault opens and he has the bearer bonds in place – something that appears in the film as a grand moment with surging music and a smiling Hans.

Then comes the road back, when the hero sees that there’s still a big challenge ahead. In Hans’s case, that big challenge is John McClane. Of course, Hans fails that challenge, thus falling off the hero’s journey. Which is only to be expected. Because while Hans might be the hero in his own story, he’s not the hero in ours.

The lesson here is, look at your story from the point of view of many characters. Perhaps use some of those story formulas when taking this look. Perhaps your villain will look like a hero from his own perspective, and perhaps something like the hero’s journey will be useful when examining it from his perspective.

This is something I often do. When structuring a screenplay, I like thinking about how the story looks from points of view other than the protagonist. This makes the other characters be more active and leads the overall plot to some interesting places. So I can recommend this approach.

So now we’ve looked at Die Hard from the perspective of these various models of story structure. So how do I view it?

I should start by saying that I am not a fundamentalist for any of these models of story structure. I think they can all have some value, but there’s always going to be great stories where they don’t apply. And they often fall short in the details.

But I do think that there’s value in looking at the acts or major sections of a story. I think Die Hard can be broken into five acts with a brief interval between two of them. The first is the setup, from the start and ending when John McClane escapes from the terrorists who have taken over Nakatomi Plaza.

The second act covers McClane’s attempt to get the attention of the authorities. It ends when the police arrive in force.

The third act deals with the arrival of the police, specifically with the SWAT team raid and the explosions of the armored car and the anti-tank gun crew.

Then comes a brief interval between two acts, where’s there’s a little bit of action to cleanse the palette and let the audience prepare for the next section. In this case, the key event of this interval is the comic fate of Harry Ellis, the dick who tries to negotiate with Hans and learns what a dumb idea that is. This presents a little breather, a brief break in the action.

But then the FBI arrives and things get serious again, and the fourth act begins. This is the climax of the pure action plot of the movie. It includes John McClane’s biggest physical challenges: his epic fight with Karl, his driving the hostages away from the soon-to-explode roof of the Nakatomi building, his avoiding the FBI’s attempts to shoot him, and the explosion that engulfs the roof of the Nakatomi building, which John escapes and the FBI does not.

Finally, we get to the fifth act, when John McClane and Hans Gruber finally face off, which is much less action-packed than the events of act four, but the stakes are at their highest, with Hans holding a gun to Holly’s head. McClane wins, reconciles with Holly, Al Powell eliminates the last loose thread by killing Karl, and John and Holly go riding off into the sunrise.

That is what I, someone not wedded to any particular screenwriting formula, see as the top level structure of Die Hard: five main acts, with a brief interval between acts three and four. I’ve added a Storylanes lane showing my view.

Of course, this doesn’t get deep into the various subplots. Each subplot has its own structure that is intertwined with the main structure.

A quick word about that Storylanes analysis. It’s available at storylanes.com. I’ve put a lot of the things mentioned here in it. It also includes little tidbits like a lane that announces when characters die, which I call the deaders lane. You can see the kind of work I put into analyzing this movie, and you might find some more interesting things to see about it. Take a look and let me know what you think.

And now we’re at the wrap-up, and we’re left with one big question. Why is Die Hard so damned good? Because I think it is, I think it’s one of the great action movies. And doing this analysis has only increased my already high opinion of it. So why, what makes it so good?

Here’s what I’ve come up with.

First, I think John McClane’s motivation to reconcile with Holly carries us through the movie. It’s believable and relatable,and it works. And when he reconciles with her in the end, it provides the right ending for this film.

Second, McClane’s actions are completely relatable and his actions are completely believable. How many times have you seen a movie where the hero faces overwhelming odds and you wonder why he doesn’t call for help. That doesn’t happen in Die Hard, because John McClane calls for help. It doesn’t do him any good, but he does it. His actions make sense.

Third, I love it when a hero’s successes lead to problems. Die Hard does a great job of this by turning the police and the FBI into major obstacles.

Fourth, and maybe it should go first, is Hans Gruber. What a terrific villain. His motivations are understandable. His actions are well thought out – he’s not just a paper tiger, he’s a genius of crime. McClane has to be better than Hans, he can’t just capitalize on Hans’s mistakes, because Hans doesn’t really make any. A great villain elevates the story, and Hans is one of the best.

Fifth, the super-scene structure and tapestry of viewpoints that I talked about, the way we bounce between different points of view during large action sequences, is a true standout. Especially given just how well they do it. This is something that’s hard to do – hard to plan out, hard to write, and the logistics of filming it are beyond difficult. What an accomplishment, and what a great effect.

Finally, any great movie needs great scenes that excite an audience and gives them something to talk about, and there many great scenes here. Sending the dead Tony down the elevator with a taunting message. John McClane climbing through the ducts. McClane rapelling on the firehose. McClane dropping the body on Powell’s car. The rooftop explosion. And the great encounter between Hans and John when Hans pretends to be a hostage. A great movie needs memorable moments, and this one has many.

Any flaws in this movie? I don’t know, maybe a few logic holes. It’s not clear why Hans decides to go check out the explosives, the action that leads to his meeting McClane. And it doesn’t really make sense that that last lock on the vault would open if the power is cut, but only cut from outside the building. But there’s nothing major, and I’m willing to give Die Hard a pass.

And I suppose there’s certainly some problematic views about Holly’s feminist choices, though the movie tries to walk both sides of that line. So it doesn’t seem like a giant deal.

So I don’t see any big flaws in this film. The action never flags, the characters remain compelling throughout, and it’s a whole lot of fun.

Finally, let’s talk a little about lessons for the screenwriter. I hope you’ve noticed a lot of them popping up in this episode. But I’ll give three of my top lessons.

First, it’s cool when the hero does what I’d do, only at a different scale. John McClane tries to call the cops, just like I would. How cool is that?

Second, it’s cool when the solution to one problem becomes the next problem. Another way to put this is that old saying: be careful what you wish for. Because how cool when the hero’s wish is granted, but it turns out bad, as happens when McClane finally summons the cops.

And third, a good villain makes a good hero. So come up with a great villain for your movie – your audience will thank you.

So that’s my analysis of Die Hard. Clearly there’s a whole lot more to say about this movie. I didn’t even get into the question of whether it’s a Christmas movie or not, a question on which I am completely agnostic. (Though I did watch it with my family this past Christmas.)

And I hope you enjoy Die Hard as much as I do, and as my family did. And I hope you’ve enjoyed this analysis as much as I have doing it. Hopefully you’ve learned something – I’ve certainly learned tons.

So thank you for listening to the Storylanes podcast. If this all works out, I’ll be publishing another episode in a week. And if things go as I hope, one of these days you may be able to use the Storylanes tool to help structure your own story. I’m working on that – I already use it on my own screenplays.

But until then, this is Joe Dzikiewicz, and check us out at Storylanes.com.