This week, we look at ALIEN, the great 70’s sci-fi horror film. Here’s the links:

- The script I analyzed.

- The original spec script for ALIEN.

- The Storylanes analysis chart.

- Listen to this episode online.

And here’s the script of this episode. (NOT the transcript – some wording was changed in the course of recording this episode.)

Hi, I’m Joe Dzikiewicz, and welcome to the Storylanes Podcast, the podcast where every week we do a deep dive into a movie or TV episode. And to go along with this analysis, every week I publish a graph of the story we’re covering on the storylanes.com website, a graph I produced while doing the analysis. You don’t need to look at that graph – the podcast is standalone. But if you’re interested in diving a little deeper, check it out at storylanes.com.

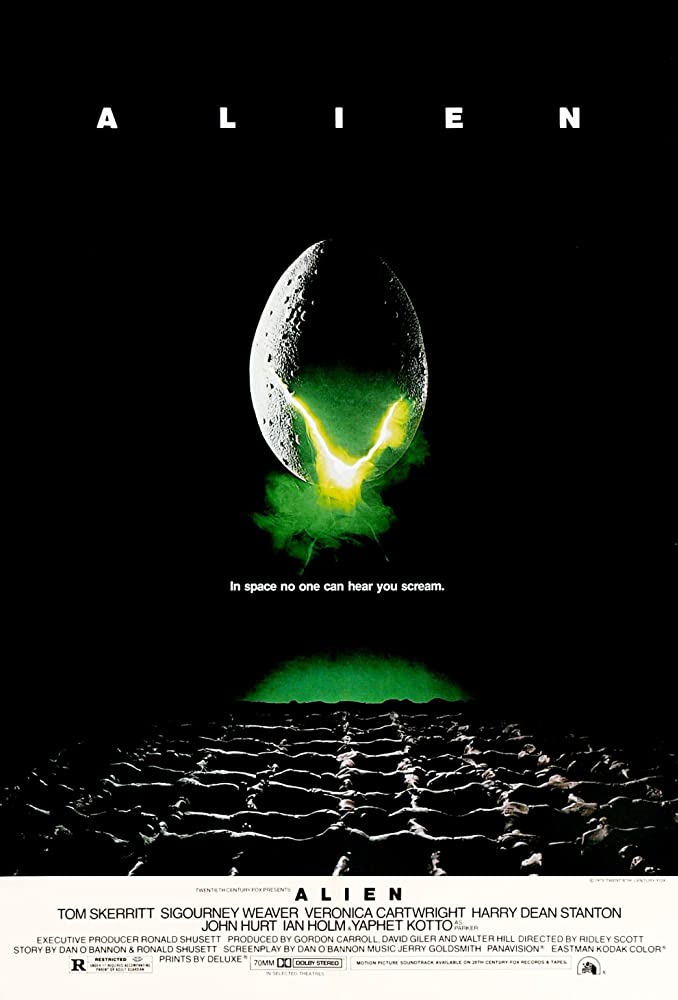

This week we’re covering ALIEN, the great science fiction horror film from 1979. The script of the final film was by Walter Hill and David Giler, but that was based on a screenplay by Dan O’Bannon, which in turn was based on a story by Dan O’Bannon and Ronald Shusett. The film itself was directed by Ridley Scott and starred Sigourney Weaver, Tom Skerritt, Ian Holm, and John Hurt.

Now, this podcast assumes you’ve seen the movie. There will be spoilers. And there won’t be detailed explanations of plot points. So if you listen to this without knowing the movie, you’re out of luck: the movie will be spoiled for you, and you may not understand what I’m talking about. So go watch the movie, if you haven’t. It’s a good one, and well worth the watching.

ALIEN is the story of the crew of the Nostromo, a run-down space freighter, that encounters an distress signal on a distant planet. They go to the planet to check things out and end up, through a truly iconic and gruesome set of scenes, having an Alien monster get on their ship. They try to get rid of the Alien, but one-by-one it kills the crew, leaving only Ripley alive. She defeats the Alien and goes back into deep sleep, on her way back to Earth and a series of sequels.

So let’s dive into what makes ALIEN special, and why it still stands out after over forty years as a classic of science fiction horror.

I think the first thing to note about ALIEN is its tone. Which admittedly is not only the script: a lot has to do with the production itself. There’s something rundown about this world and these characters. The Nostromo is described as a “Commercial towing vehicle,” about as unglamorous a description as a spaceship can have. And it’s clear that the crew is nothing special: they’re a bunch of working-class stiffs, middling competent at their jobs. Not by any imagination an elite crew. They’re about what you might expect of a modern crew on a cargo ship – sufficiently good at their jobs to take a ship on a months-long voyage, but not the people you would choose to put on the front lines if civilization were at stake. Competent, but not heroic.

And so their approach to this crisis that they face is a little haphazard. They’re improvising, making it up as they go along. Trying to get the job done.

The Nostromo itself is very much in keeping with this rundown vibe. The corridors aren’t well lit, the control systems don’t inspire awe, the corridors aren’t all that clean, and the engines are likely to break if you put the least strain on them. The Starship Enterprise this ain’t!

And while this may not have been the filmmaker’s intent, take a look at that computer tech. It’s cutting edge for 1979, but sure looks clunky today, with its black-and-green screens and crude line-drawing graphics. For a modern viewer, it adds to the rundown feel of the Nostromo. We’ve all got better computers in our pockets than the Nostromo’s crew use to run the ship!

Much of Alien has a real cinema verité style to it. It feels like this is a fly-on-the-wall documentary and we are watching a bunch of working folk just doing their jobs. It’s only later in the film, when the Alien hunt goes full-swing, that things start to get more cinematic.

And in the early part of the film, we focus a lot on the mechanics of what they are doing. We see Parker and Brett and the hard work they’re doing to fix the ship. We see the mechanical aspects of the ship as it couples and uncouples from the huge cargo vessel that it’s towing across the galaxy. We see the crew grumbling about their mundane concerns, about bonuses and the quality of the food.

All of this grounds the film and makes it feel real. Sure, these people are in a spaceship. And sure, they’re fighting some weird alien monster. But it feels real because these people are so grounded – they may live in a science fiction world, but because it’s not special to them, it feels real to us.

One thing I want to note about this tone. For me, the movie has a real 2001 feel. Like in 2001, the movie spends a lot of time showing how this science fiction tech works. And like 2001, it all feels quite real.

But ALIEN is a much more lived-in world than 2001. While 2001 felt slick and cutting edge, ALIEN feels old and well-used. To that extent, it has a STAR WARS feel. Like the Millennium Falcon, the Nostromo feels like people have lived in it for years, tossed their dirty laundry in the corners, and kept things together with baling wire and duct tape. Though, of course, the Nostromo is a much less romantic ship than the Millennium Falcon. In fact, it’s hard to imagine a less romantic spaceship than the Nostromo.

And as just one example, look at Kane’s funeral. Nobody speaks any words. They just dump his body into space with about as much ceremony as they might use tossing out the garbage. It’s got to be one of the least emotional funerals in film history.

In terms of the science fiction aspects of it all, ALIEN feels to me like 2001-levels of technical realism and detail combined with the lived-in quality of STAR WARS. And that tone is one of the unique things about this film.

Though I should note, it was very much part of its time. Although I don’t know of any significant science fiction movies of the time that had such a strong cinema verité feel, there were plenty of other films that had that tone. I’m thinking of THE FRENCH CONNECTION, a cinema verité cop movie, or MASH, a cinema verité war movie. ALIEN seems very much in that vein.

So the tone is one of the things that makes ALIEN stand out, especially when compared with the more polished films that followed in the eighties. But the other big element that distinguishes this film is the Alien itself.

I believe that the Alien of ALIEN is quite probably the greatest monster design in cinematic history. It was instantly iconic and has influenced monster design ever since. The hard carapace, the nested mouths, the slimy ichor. That’s a great design.

And that’s not getting into the elements of the creature design that affect the plot. Those too are marvelously compelling. It’s lifecycle, clearly, is a standout. This is the lifecycle of a wasp. It plants eggs within its prey, and when the egg hatches the larva feed on that prey and eventually emerges. That’s pretty horrible when the prey is a horn worm. Darwin himself found his faith shaken by this: he wrote, “I cannot persuade myself that a beneficent and omnipotent God would have designedly created the Ichneumonidae with the express intention of their feeding within the living bodies of caterpillars.”

And if it’s that horrible to imagine being done to a caterpillar, imagine how horrible it is being done to a human. Or don’t imagine – just watch ALIEN.

This is a brilliant touch. It’s viscerally disturbing and leads to one of the most disturbing and iconic scenes in movie history, the chest-burster scene. People walked out of ALIEN during that scene. It still has an impact.

And the Face-Hugger form, the first form of the Alien that we see, is equally disturbing. Especially when you realize what the Face-Hugger is doing – planting its egg deep into Kane.

This design of the Alien’s lifecycle is enough to make it one of the most disturbing monsters in movie history. The iconic design of the Alien just adds to it.

There are, of course, other terrific aspects of the Alien. For example, the molecular acid for blood, which means that the crew of the Nostromo can’t just shoot the thing or its blood will burn a hole through the hull, is a marvelous touch and makes it believable that one creature can cause so much trouble for a crew in a science fiction world.

All in all, ALIEN creates an amazing monster that is viscerally disturbing, hard to defeat in the circumstances of the film, and a delight to view. It is truly one of the things that makes this movie special.

So, with the tone and the Alien dealt with, let’s turn to the characters.

The characters are distinct and stand out as individuals, but there’s definitely a subdued tone to them that’s in keeping with the rest of the movie. These are not your traditional heroes: they’re working class types just doing a job. And even when things go crazy, they just do the best they can to make it through.

Ripley, in particular, is fascinating for a lot of reasons. First off, it takes a long time before she emerges as the protagonist. She doesn’t take the lead early on. She doesn’t go on the trek to the alien spaceship and she’s not at the forefront of coming up with plans. She doesn’t really stand out, except for a bit of a tendency to be stubborn and careful. It’s hard to see her as protagonist until Dallas dies, which doesn’t happen until page 73 of a 112 page screenplay – almost two-thirds into the movie!

Second, there’s the fact that she’s an uncompromising badass female action-movie protagonist. Sadly, this is still rare, and was even more rare then.

With that said, Ripley has a lot of good qualities for an action hero. She’s decisive, she stands by her opinions, she challenges others for doing what she thinks is wrong. Note how she calls Ash to task for letting the away team into the ship, violating quarantine rules and jeopardizing the crew. Or how she challenges Dallas for backing Ash in the decision to keep the dead Face Hugger.

So all in all, Ripley is an excellent protagonist, but the way she emerges as such is organic and completely believable – something very much keeping with the tone of this movie.

In most movies, Dallas, the captain, would be the protagonist. But while he’s a terrific character, he does come up a bit short as an action hero. He lacks the headstrong nature we expect of our action protagonists. He is not as decisive as he might be – note again how he defers to Ash about what to do with the Face Hugger. And he certainly doesn’t demonstrate any special talents. Dallas is no John McClane.

Ash is a wonderful character and provides a good dose of conflict. He isn’t obviously a villain, but he’s always subtly pushing his dangerous agenda of letting the Alien into the ship. And he is clearly isolated from the rest of the crew – he’s always the guy on the outside, looking in. When Dallas, Kane, and Lambert go off to the Alien ship, and Ripley, Parker, and Brett are working on the ship, Ash sits alone in his little corner of the Nostromo coldly dealing with computers and monitors.

Further, Ash is the only one of the crew who comes into this film with a solid strong want. He wants to follow his orders and bring the Alien home. And once you know that’s what he wants, you can see all of his actions in that light. Allowing the Face-hugged Kane into the ship. Preserving the Face Hugger. Working subtly against the crew’s attempts to space the Alien – though that’s something that comes through stronger in the script than in the finished film. He’s a delight.

The rest of the crew are solid characters. They are individuals without being special.

Parker as the mouthy guy who works the system – note how, when he’s asked how long a job will take, he pads Brett’s estimate. But in the end, Parker may grumble, but when the chips are down he delivers, both building flamethrowers as needed and attacking the Alien mano a mano in an attempt to save Lambert.

Brett, Parker’s sidekick, makes fun of his own subservience when he plays up the “Right” after people complain that’s all he says. But given that Parker defers to him when it comes to repairs, you suspect that there’s a bit more intelligence there than meets the eye. Or maybe not.

Lambert is the steady worker who panics in a pinch. Of course, there’s some good reasons to panic – but it’s nice that someone gets to show a little fear.

Kane doesn’t really stand out. But then, he spends most of the movie either dead or unconscious, so it’s not surprising that he doesn’t have time to leap off the page. Though he does get to star in the two truly iconic moments of this film, the Face Hugger and Chest Bursting scenes, so don’t feel too sorry for him!

All in all, a low-key believable crew. They’re not the larger-than-life figures we’d expect from an action film in the 80’s and beyond. But for this cinema verité world, they’re perfect.

So screenwriting lesson. Your characters should reflect the tone of the film you’re making. If you want to make something low-key, by all means come up with characters who aren’t heroic standouts. And this can work especially well if you want to show what happens when regular people have to deal with vastly irregular events, as happens here: part of the fun of ALIEN is seeing just how these normal people deal with the vastly abnormal Alien.

Now let’s talk about the plot.

The one thing that really stands out to me about ALIEN is what a slow burn it has. For the first full half-hour of the film, we see the crew of the Nostromo going through their regular routine. Sure, there’s small conflicts. Parker and Brett want to be paid more. The ship is damaged on landing. The crew isn’t happy to still be far from Earth, and the food isn’t much good. But for the most part, we’re just watching day-to-day life on a spaceship. It’s hard to imagine a more modern film taking so much time before things really get rolling.

The Face Hugger scene doesn’t occur until 31 pages into the screenplay, a full 35 minutes into the movie. Now things really start moving. But even then, it’s another 28 pages of screenplay before the Chest Burster scene. The main Alien form doesn’t appear until a full 57 minutes into this two-hour movie.

But from then on, we’re on a rocket sled. In fairly quick succession, we get the deaths of Brett and Dallas, we get the climax of Ash’s treachery, then we get Ripley’s escape and final battle with the Alien.

But again, it’s hard to imagine a more modern audience being okay with taking so long to get down to business. But it might work. So screenwriters, feel free to try writing something with this kind of slow burn, but bear in mind you might have trouble convincing an audience or a producer to give you this much time. And after that wait, you better have something worth waiting for! (And I think we can all agree that the Face Hugger and Chest Burster scenes were worth waiting for.)

Now let’s look at the structure beyond the slow burn. And to do this, I’m going to jump ahead a little and look at ALIEN in terms of three act structure. Because I think this film adheres fairly well to classic three-act structure. And there is, not surprising, a lane for three-act structure on the Storylanes analysis at storylanes.com.

The first act, the setup, takes us all the way to the Face Hugger scene. This establishes the world, introduces the characters, and sets up the basic problem of the film. In this case, the film is all about checking out the cause of the distress signal that wakes up the Nostromo.

And in fact the distress signal is the inciting incident of the film. Now, you could argue that the true inciting incident occurred before the movie starts. After all, the ship received the signal, which caused it to wake up the crew.

But the crew doesn’t discover the signal until Dallas receives it from Mother, the computer. That happens on page 9 of the screenplay, so roughly 9 minutes into the movie. At that point, the crew starts doing the actions that result in the film.

So what happens in act one? The crew wakes up, they receive the distress signal, they land the Nostromo on the planet, and the ship is damaged during landing, Dallas, Kane, and Lambert go out to find the alien ship while Ash monitors and Parker, Brett, and Ripley repair the ship.

All of this is background and setup.

And then comes the Face Hugger scene. And that catapults us into act two. Suddenly there’s a problem – this weird alien thing stuck to Kane’s face. But at this point, it doesn’t seem like this is a life-and-death crisis. Weird, sure. And maybe Kane is in trouble. But still relatively low stakes.

What follows are three sequences of increasing risk that build tension and conflict. The first is the return of the landing party to the ship. When they get there, Ripley doesn’t want to let them in: allowing them in violates quarantine rules and could put the entire crew at risk. But Ash overrides her and opens the door. We don’t know it yet, but he’s acting on his own imperative: bring the Alien home. But now the sequence is over, and the Face-Hugger is in the ship.

The next sequence occurs when they try cutting the Face Hugger off of Kane and it bleeds acid. The acid burns its way through the decks of the ship, luckily burning out before it reaches the hull. But there’s a real moment of concern as the acid drips its way through deck after deck. And at the end of this sequence, they decide that there’s nothing they can really do to get the Face Hugger off of Kane.

The third sequence starts when Ash reports that the Face Hugger is missing. Ripley, Dallas, and Ash search the infirmary for it. Then the Face Hugger drops on Ripley – a jump scare that leads to nothing when it turns out to be dead.

So we have these three sequences, all related to dealing with the results of the Face Hugging scene. Kane with the Face Huggers is brought into the ship. The Face Hugger’s acid blood is discovered and dealt with. And finally, the Face Hugger is off Kane. And now, we’re midway through the movie.

Here too ALIEN adheres fairly well to traditional three-act structure. Because we’re at the midpoint, and hoo boy, is this midpoint a doozy!

That’s the Chest Burster scene. A huge moment that dramatically escalates the conflict and shapes the rest of the film. And it happens on page 57, almost the exact midpoint of this 105 page script.

And really, it’s hard to think of a more consequential midpoint in all of cinema. The only other midpoint of this magnitude that springs immediately to my mind is the shower scene in PSYCHO.

And now the stakes are suddenly higher. For the first time, a crew member has died. And there’s a little alien creature loose on the ship.

After the midpoint, through the rest of Act Two, we again have three major sequences with escalating consequences. First, the crew starts going through the ship with nets and cattle prods, trying to catch what they think is a tiny Alien. Only the Alien isn’t tiny any more – somehow it’s grown to larger-than-human size, and it kills Brett. So escalation: the small alien is now a large alien, and an obvious threat to the life of the crew. And that crew is now down to five.

In the next sequence, the crew comes up with a plan to flush the Alien out of the ducts into an air lock where it can be blown into space. There is definitely escalating tension: now the crew isn’t hunting a baby creature with nets and cattle prods, they’re going after a large deadly monster with a flamethrower.

But that doesn’t work out. And scratch another crew member, this time Captain Dallas.

In the next sequence, we break the pattern. Instead of having another scene of escalating Alien action, the big threat in the next sequence is Ash. Ripley, who with Dallas’s death has now emerged as our protagonist, confronts Ash with evidence that Ash has been working against the crew. And that confrontation quickly turns physical. In fact, Ash almost kills her and is only stopped when Parker appears and knocks his head off, revealing that Ash is in fact a robot.

This is an escalation because Ripley is now clearly the protagonist, and this is the first time her life is at risk. And the end result is that the crew now knows that the Company that employs them set them up. With that revelation, the surviving crew members decide to leave the Nostromo in the shuttle, fleeing the Alien. And with that plan made, we now move into act Three.

But note the overall structure of this. Act two is broken into six sequences of escalating risk and conflict, separated into two groups of three sequences by a powerful midpoint that itself drastically escalates the stakes. There’s something delightfully symmetric about this second act. It’s a remarkably clean structure.

And a screenwriter note: you don’t need this clean a structure. But it obviously works.

What you do need is escalating stakes and tension. But the stakes don’t have to escalate at a steady pace. In ALIEN, there is a dramatic rise in stakes at the midpoint. Which is, of course, the whole reason to have a midpoint. But this escalation could be done at some other pace.

And now we’re in Act Three. And it’s a fairly traditional act three. Our protagonist has a plan, to abandon the ship. Now all she has to do is execute on it.

ALIEN’s act three demonstrates a number of tricks that escalate tension. First, the Alien kills Parker and Lambert, leaving Ripley on her own. Next, Ripley takes a risk to rescue an innocent, in this case Jones the cat. Then Ripley starts the self-destruct mechanism of the Nostromo, which comes with a nice clock that sets a deadline and continuously counts down – which is always a terrific tension builder.

Then Ripley seems to have escaped on the shuttle, only to find that the Alien is also on board. So we need one last epic fight between Ripley and the Alien to blow it into space, where Ripley can torch it using the shuttle’s engines.

This is pretty much a textbook act three. Isolate the protagonist. Show her character by having her take a risk for someone else. Throw in a clock to race. Have the monster appear unexpectedly at the end. Have the protagonist show her merit by winning one final battle. All quite good, and all extremely effective.

So, Alien sticks quite closely to three act structure. And it does it quite well indeed.

Before we look at other screenplay models, let’s take a quick look at subplots.

There aren’t a whole lot of subplots in ALIEN. In fact, I’d say that there is only one fully developed subplot: the treachery of Ash. Or, as I like to call it in the Storylanes analysis, Ash-hole.

Early on, this subplot largely appears in the way that Ash is isolated from the rest of the crew. He is always sitting alone in his hidey-hole working on his computers. And he shows a certain disinterest in the regular goings-on in the ship and in his fellow crew.

He also acts subtly in ways to undercut any actions that would work against bringing the Alien on board. That includes discouraging Ripley from telling the Away Team that the distress signal is in fact a warning. It also includes letting the Away Team with the Face Hugger into the ship, violating the quarantine rules, and his lack of repentance when Ripley confronts him about this. He offers no concrete solutions to defeat the Alien, only opposition. And of course this subplot climaxes when Ash attacks Ripley, the revelation that he is a robot, and his post-mortem interrogation in which he reveals the company’s treachery.

This subplot does a couple things. First, it helps undercut possible complaints that the crew is acting dumb. Yes, it’s dumb to let the Face Hugger back on the ship. But Ash has his reasons, and they are not at all dumb, only treacherous.

But second, and possibly more importantly, it gives another big source of conflict and opposition. As I noted, the fight with Ash is a different kind of conflict. It provides a nice break from repeated battles with the Alien.

So screenwriter note: give another source of conflict, because the primary source can get boring.

A second subplot is labor unrest among the crew, though this isn’t developed at all. It’s mainly Parker and Brett complaining early on that they are not paid equally with the others. It’s dropped as soon as the Alien appears, and dies along with Brett.

I think the main purpose of this plot is to add a little conflict in the long first act, before things really heat up. It’s just a little friction, but it keeps things spicy. And it gives some character definition to Parker and Brett.

So if you’re going to do something with a slow burn like Alien, consider adding a subplot with a little conflict to carry you through the slow parts. You don’t have to keep it around forever, but it can help in the early going.

In the Storylanes analysis, I listed a subplot of Ripley as Protagonist. It’s not really a subplot per se, but I wanted to add a place where I noted the signs of Ripley emerging as protagonist.

And now we have the final subplot that you’ll see on the Storylanes analysis. And this is interesting largely because it’s a subplot that’s in the script but that got cut from the final film.

The script has a sexual relationship between Ripley and Dallas, including a scene where the two have some recreational sex. It doesn’t imply any kind of romantic relationship, but the two definitely hook up.

Then there’s another scene, late in the script, where Ripley comes across Dallas deep in the ship. Dallas is cocooned in Alien goop, and while Ripley wants to free him, he begs her to instead kill him. Apparently the Alien captured him and laid some kind of egg in him. But he’d rather be killed now have to go through any version of what Kane went through. And really, who can blame him?

I’ll note: I could swear I saw a version of that scene once. I actually saw this movie in the theater when it first came out, so it’s possible I saw it then. Or it’s possible that I’m just not remembering correctly – I also read the novelization of the film way back when, and I might just be remembering that. I suppose Mister Internet probably knows if that scene was ever shot and, if so, if it was ever in the film. But I’m not going to ask him. Not right now, anyway.

Anyway, you can see how this subplot could have added a touch of personal relationships to this film. But you can also see that it’s not needed – the film gets along okay without it. And while I feel that I can see a bit of a deeper relationship in the scenes in the film between Ripley and Dallas, it’s not so strong that I’d swear that it’s there.

Next, the theme of Alien. And that is… well, honestly, I’m not quite sure. It’s dangerous out there? The unknown is full of strange risk? We’re ultimately all alone in the universe? All of those are present, but none of them seem so strongly present that I’d call them a theme.

Maybe you don’t always need a theme. Maybe with enough tone and a cool enough monster, you can get by without.

So now let’s see how ALIEN fares considered against some other screenplay models.

Let’s start with Blake Snyder’s Save the Cat. But before I get into what it has to say about ALIEN’s structure, I want to take a moment to discuss saving cats.

Snyder named his book “Save the Cat” because he states that it’s important to make a protagonist sympathetic early in the movie, and one good way is to show the protagonist doing a good deed early on. Snyder uses saving a cat as a metaphor and example of this: seeing someone save a cat early in the film puts you on that person’s side.

Now I don’t believe that a protagonist has to be likable. So I don’t believe that doing an early save-the-cat type action is required.

And in fact, Ripley doesn’t save a cat in the first act of ALIEN. But later in the film she literally saves a cat, Jones, and risks her life in doing so.

Now I’m sure the ALIEN writers didn’t have Blake Snyder in mind. After all, “SAVE THE CAT” wasn’t published until over 25 years after ALIEN was released. But it still makes me grin.

And it does work. Ripley’s willingness to risk her life for Jones does make her more sympathetic, especially after we’ve spent the entire film seeing her as a bit of an uncaring badass.

But that aside, how does SAVE THE CAT stack up against ALIEN?

Pretty good. Not surprising – after all, SAVE THE CAT just expands on three-act structure, and as we’ve discussed, ALIEN adheres fairly closely to three-act-structure. But ALIEN also has most of the other save-the-cat beats, and the page numbers aren’t that far off.

There’s the opening image, that sets the mood and tone of the film. In the case of ALIEN, it’s a ship traveling quietly alone through space. So we have the sense of isolation that feeds into the film – the idea that these people are all alone, far from any help, as they deal with the ALIEN threat.

There’s a set-up period, that sets up the location and the characters. This is the tour through the empty corridors of the Nostromo, followed by the introduction of the waking characters. Snyder says this section should cover pages 1-10, in ALIEN it covers 1-8. Close enough.

Then there’s the Catalyst, which is what Snyder calls the Inciting Incident. That’s Dallas discovering the distress signal. Snyder has this at page 12, in ALIEN it’s on page 9.

Snyder has a period he calls the Debate, in which the protagonist wrestles with the question of whether or not to act on the inciting incident. Snyder says this should cover pages 12-25. ALIEN has that beat, but it only takes a moment: the crew argues over whether they should follow up on the distress signal, but Dallas informs them pretty quickly that they are required to do so. So the beat is there, but it certainly doesn’t cover 13 pages.

And finally we have Snyder’s break-into-two, which he puts at page 25. In ALIEN, it’s page 30. Pretty close.

Snyder’s next beat is the B story. In the case of ALIEN, the B story is Ash’s treachery. And that really starts when Ash lets the away team with the Face Hugger into the ship. That’s on page 34 of the script. Snyder has it at 30.

Snyder calls his next section fun-and-games where there’s action and events, but the stakes are still pretty low. I’d say that’s all the shenanigans that arise between the Face Hugger and Chest Burster scenes. So pages 30-57. Snyder calls it page 30 through 55 – almost perfect.

And then is the midpoint. Snyder says page 55, the Alien script says 57. Not bad!

That starts a section that Snyder calls “Bad Guys Close In,” from page 55 through 75. That’s the growing tension that occurs before it seems that all is lost. Here again, Snyder is pretty good – I’d make this as being pages 57 through 80 in the ALIEN screenplay.

On page 75, Snyder says we’re at the All is Lost moment, where it seems like the heroes will never win, and where a period of despair, the Dark Night of the Soul, sets in. In ALIEN, this seems to happen when Dallas is killed. Their plan failed. Their leader is dead. Their opposition is worse than they imagined. And they’re about to discover that Ash, one of them, is a traitor. It’s a pretty low moment, and a pretty deep dark night of the soul. And again, Snyder almost pinpoints the page counts. Snyder has this period going from page 75 through 85. In ALIEN, it’s page 80 to 93. Pretty dang close.

Then we have the break into act three, which in ALIEN occurs at page 93, only a little later than Snyder’s prediction of page 85. And we’re in the finale.

Finally, Snyder has a final image, which he calls for page 110 but in Alien is on page 105. Snyder says that this image should be the opposite of the original image and show that something has changed.

But that’s not how ALIEN uses its final image. The final image of Alien shows the shuttle flying off alone into space. Once again, a ship is all alone in the middle of nowhere. Even more alone – it’s a smaller ship and we know only one crew member is left. So sorry, Snyder – while you got the page number right here, you missed the meaning.

So Snyder did pretty good with ALIEN. The page numbers aren’t exactly right, but they’re close. And almost all of his beats are present.

About the only Snyder beat I don’t see here is the stating of the theme. But as I noted, ALIEN doesn’t seem to have that strong a theme.

And that leads us to the Hero’s Journey. Here too ALIEN is a good match. About the only beat that’s missing is the Meeting the Mentor beat – there are no mentors in ALIEN.

But early on, before Ripley clearly emerges as the protagonist, when considering the Hero’s Journey we have to look at the entire crew as the hero. With that caveat, things proceed fairly nicely along the hero’s journey. There’s the establishment of the status quo – the world of the Nostromo. The call-to-adventure, when the distress signal is received. A quick refusal of the call as the crew argues over whether to respond to the signal. And all the act two beats show up nicely.

Though it’s worth noting that from a Hero’s Journey perspective, the ordeal, in which the hero faces the biggest test, is the fight against Ash. And thus, Ash is the biggest challenge in Alien. I suppose one could make an argument for that. But I still think that the Alien is more dangerous. (Though Ash comes closest to killing Ripley, so maybe…)

The Hero’s Journey really shines in act three. The hero goes on the Road Back, in this case the return to Earth on the shuttle. But then the Hero sees a huge challenge ahead. In this case, that’s the Alien who has stowed away on the shuttle. The Hero overcomes that challenge, then returns with the prize. In this case, the prize is Jones, the cat. Maybe not that much of a prize, but Ripley seems happy to have him.

Finally, how do I view the structure of ALIEN? Well, I have my doubts about midpoints. In particular, I don’t see why one insists that one must have one long Act Two with a great big midpoint, instead of just saying that there are two middle acts that are separated by that midpoint.

So I’d describe ALIEN as having four acts. Act One is the opening, ending with the Face Hugger scene. Then Act Two covers the results of the Face Hugger scene and climaxes with the Chest Burster scene. Act Three is the fight against the Alien and ends with the destruction of Ash and the plan to flee the ship. And Act Four is the climax, the final fight against the Alien, ending with the end of the film.

That’s my take, anyway. I won’t editorialize more about three-act-plus-midpoint vs four-act structure. Suffice to say that I have opinions.

Now, a quick note on the Storylanes analysis. I wasn’t as careful this time of breaking things into individual scenes and sluglines. I often grouped sluglines when I thought it made sense to view a group of scenes together. I hope you like this approach – I think it makes the graph easier to follow and to use.

I also included the Deader lane, like I did with Die Hard. It made sense here to indicate where each character died.

I also included a lane called Film vs Script. There were a number of differences between the script I worked with and the final film of Alien. Several scenes were in the script but not in the movie. Some shots were in the movie but not the script. I always find it interesting to see how things change in the final movie, so I called out some of these. I hope you find them interesting.

So, now we’re at the wrap-up. What do I think of Alien?

I like it. It’s a terrific movie. Good suspense, terrific thrills, some truly original stuff.

So what’s best about it?

First, the Alien. One of the best designed monsters in movie history. Maybe the best. And the lifecycle – wow, how amazing! The way its larval stage lays eggs in a human. The Face Hugger form. The Face Hugger scene. The Chest Burster scene. All good stuff.

Second, this particular corner of the future. The working-class ethos of the Nostromo. The cinema verité style. The ship itself, grungy and cool.

Third, this movie gets the basic mechanics of suspense and structure down pat. Lots of good suspense moments. Good jump scares. Good red herrings. And a solidly constructed act three that pushes all the right buttons.

Anything wrong?

Well, yeah. There’s lots of logic holes in this film. Does the company know there’s an Alien monster here? If so, how? If not, why is Ash so hot on getting the Alien and not the rest of the Alien tech in the ship?

And why oh why does the Nostromo have a self-destruct system? My car doesn’t. Does any vehicle in the real world have a system built into it to blow itself up? I’ve never heard of such a thing in the real world, for all that it’s a trope in fiction.

And if you’re going to have a self-destruct mechanism, I can see why you might want to make it require many steps to set off, as happens with the Nostromo. After all, you don’t want anyone just accidentally blowing up your ship. But why in the world would you make it equally hard to turn off the self-destruct, as is the case here? Remember, at one point Ripley decides to stop the self-destruct sequence, but she can’t get all the convoluted steps done on time to stop it, so she’s forced to race against the clock, to get off the ship before it explodes. That makes no sense.

And how the heck did the alien grow from the tiny thing that popped out of Kane’s chest to the giant monster that captures Brett? That’s a bit leap with no explanation given.

But my least favorite logic hole in Alien is this. After the Chest Burster scene, when the crew breaks into two teams to hunt the Alien, they get into teams of three so that none will be alone. That makes perfect sense to me – you don’t want someone running off alone when there’s a dangerous creature running lose.

But then Parker, Brett, and Ripley run into Jones the cat, so they send Brett off alone to capture him.

What?

Why don’t they all go? This is in complete violation of the reason they kept together in the first place! And the first time I saw Alien, as soon as I saw Brett go off alone, I knew he was Alien chow.

It’s the oldest stupid trope in horror films. Leave the group and go off alone when there’s a monster around and everyone knows what’s going to happen to you. ALIEN is too good for that nonsense. Except, sadly, it isn’t.

And the last: let’s look for three screenwriting lessons in ALIEN.

First, in a horror movie, the monster is everything. Come up with a great monster and you’ve got horror gold.

Second, if you can come up with a truly great scene, something horrific that will shape the entire course of your film, consider making it the midpoint. That’s an awfully effective place for it.

And third, even if you have the greatest monster in movie history, it’s useful to have another source of conflict. Have a major sequence where the conflict comes from something other than the monster. The change of pace will do wonders for your film.

So that’s ALIEN. A terrific science fiction horror movie, very much of its period. And a lot of fun to watch, and to analyze.

I hope you enjoyed this as much as I enjoyed doing it. And next week, we’ll take a look at the sequel to ALIEN. Which is, of course, ALIENS. One of the more interesting sequels in movie history, in that it is so different in tone and style from the original. And while ALIEN is very much a movie of the 70’s, with its nitty-gritty realistic style and tone, ALIENS is all 80’s – big heroic characters and plenty of stylish action.

So check us out on Storylanes.com, and you can see the Storylanes analysis of ALIEN.

Talk at you next week!